Abel Janszoon Tasman, 1603?–1659

First Expedition (1642): Two ships (Heemskerck and Zeehaen), 110 men

Charge (by the Dutch East India Company): To search for the Southern Continent

Accomplishments: Discovered Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), New Zealand, Fiji Islands

Second Expedition (1644): Three ships (Limmen, Zeemeeuw, and Bracq), 94 men

Charge (by the Dutch East India Company): To find a passage between Carpentaria and New Guinea into the South Sea (Torres Strait, which he missed)

Accomplishment: Charted the northern coast of New Holland (Australia)

Legacy of Tasman’s name: Tasmania (island state of Australia), Tasmanian Devil (species), Tasmannia (plant), Abel Tasman National Park (New Zealand), among others

[Click on the images below for high resolution versions.]

Portrait of Abel Janszoon Tasman. From vol. 8 of The Pall Mall Magazine (London, 1896). [General Library Collection]

A captain in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), Tasman was commanding a trading vessel out of Amboina in the Moluccas (Spice Islands) when, in 1639, he was tapped for a voyage of exploration to the North Pacific Ocean. The VOC hoped to find two fabled islands, Rica de Oro (rich in gold) and Rica de Plata (rich in silver), east of Japan. The six-month voyage, along today’s Philippines, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan, and into the Pacific for a great distance, discovered nothing of commercial value, but it provided Tasman with valuable exploring experience in unknown seas and brought his abilities to the attention of Anton van Diemen, governor-general of the VOC in Batavia (today’s Jakarta, Indonesia).

Desiring to expand his company’s trading opportunities, Van Diemen commissioned Tasman to undertake a new voyage to seek southward and eastward for the legendary Southern Continent and then, moving north, to determine whether the west coast of New Guinea was joined to it. (For more on the great “Southland,” see the Terra Australis box in the Pacific Ocean section.) The scope of this ambitious project necessitated, ultimately, two separate expeditions.

On August 14, 1642, Tasman departed from Batavia with two ships, the Heemskerck and Zeehaen, sailing west to Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. From there, taking advantage of the winds, they were to turn south to about 54°, further south than anyone had gone before, and comb the ocean eastward. However, around 45° they encountered very misty, hence dangerous, conditions and determined to sail more easterly—essentially sailing under Australia—and sighted new land on November 24, at a latitude of 42° S and a longitude of 163° E (from Tenerife in the Canary Islands). The surf was rough, but the ship’s carpenter managed to swim ashore, plant a flag, and take possession for the Netherlands and the VOC; Tasman named the territory Van Diemen’s Land (today’s Tasmania), after the governor-general. (The names of Tasman’s ships survive in the names of two mountains that were first sighted.) They eventually landed in December in the vicinity of today’s Hobart and found evidence of human habitation but saw no one.

"Anthony Van Diemens Landt (Tasmania). From Tasman's Abel Janszoon Tasman's Journal . . . (Amsterdam, 1898). [Rare Books Division]

Book:

Tasman, Abel Janszoon. Abel Janszoon Tasman’s Journal of His Discovery of Van Diemens Land and New Zealand in 1642, with Documents Relating to His Exploration of Australia in 1644. . . . Amsterdam, 1898. Facsimiles of the original manuscript, with an English translation by J. de Hoop Scheffer and C. Stoffel and five oversize maps in rear pocket. First full published account of Tasman’s first expedition. [Rare Books Division]

Discovery of Tasmania

[November 24, 1642] In the afternoon, about 4 o’clock, we saw land, bearing east by north of us, at about 10 miles’ distance from us by estimation; the land we sighted was very high: towards evening we also saw, east-south-east of us, three high mountains, and to the north-east two more mountains, but less high than those to the southward; we found here that our compass pointed due north. . . . [English translation section, p. 11]

This land being the first land we have met with in the South Sea, and not known to any European nation, we have conferred on it the name of Anthoony van Diemenslandt, in honour of the Hon. Governor-General, our illustrious master, who sent us to make this discovery. . . . [p. 12]

[December 3, 1642] When we had come close inshore in a small inlet which bore west-south-west of the ships, the surf ran so high that we could not get near the shore without running the risk of having our pinnace dashed to pieces. We then ordered the carpenter aforesaid to swim to the shore alone, with the pole and the flag, and kept by the wind with our pinnace; we made him plant the said pole with the flag at top into the earth, about the centre of the bay near four trees easily recognizable and standing in the form of a crescent. . . . [T]he carpenter aforesaid thereupon swam back to the pinnace through the surf. This work having been duly executed, we pulled back to the ships, leaving the above mentioned as a memorial for those who shall come after us, and for the natives of this country, who did not show themselves, though we suspect some of them were at no great distance and closely watching our proceedings. [p. 16]

“Moordenaers Bay” (Murderers Bay, New Zealand). From Tasman's Abel Janszoon Tasman's Journal . . . (Amsterdam, 1898). [Rare Books Division]

- (A) Our ships.

- (B) The prows w hich came alongside of us.

- (C) The cock-boat of the Zeehaen, which came paddling towards our ship, and was overpowered by the natives, who afterwards left it again owing to our firing; when we saw that they had left the cock-boat, our skipper fetched it back with our pinnace.

- (D) A view of the native prow with the appearance of the people.

- (E) Our ships putting off to sea.

- (F) [Refers to the next page drawing] [p. 21]

Continuing eastward, Tasman’s ships soon came upon another uncharted land, today’s northwestern part of New Zealand’s South Island, on December 13. In the first European encounter with native New Zealanders (Maori Indians), four of Tasman’s men were killed. He named the place Murderers’ Bay (today’s Golden Bay). Not realizing that a strait (Cook Strait) separated the South and North Islands, they moved northward along the coast and named the new land Staten Landt (Statesland), thinking it was the west coast of the island that fellow countrymen Jacques Le Maire and Willem Corneliszoon Schouten had discovered off the southern tip of South America in 1616. (For more on this, see Le Maire/Schouten in the Explorers section.) Tasman thought this was the western side of the great Southern Continent.

From there, sailing northwestward, the expedition located the Fiji Islands but could not land because of wind conditions and a hazardous reef. On his return to Batavia, Tasman’s arc took him past Ontong Java, New Britain and New Ireland (which he mistook as one island), and the northern coast of New Guinea. He arrived back safely on June 15, 1643, having covered more than five thousand miles in mostly uncharted waters. Not realizing it, he had completed a circumnavigation of New Holland (Australia) and proven that it was not the Southern Continent.

Discovery of New Zealand

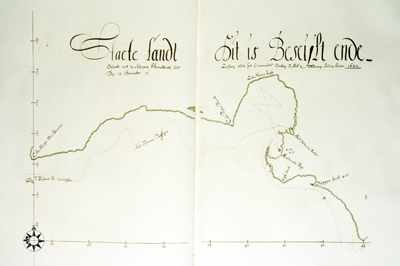

"Staete Landt Dit is Beseijlt ende" (New Zealand). From Tasman's Abel Janszoon Tasman's Journal . . . (Amsterdam, 1898). [Rare Books Division]

[December 13, 1642] Latitude observed 42°10′, Longitude 188°28′; course kept east by north, sailed 36 miles in a south-south-westerly wind with a top-gallant gale. Towards noon we saw a large, high-lying land, bearing south-east of us at about 15 miles’ distance. . . . [p. 17]

François Valentijn, 1666-1727. “Staeten Landt bezylt en ontdekt . . . (&) Aldus vertoont zich het Drie Koningen Eyland . . . .” Copperplate map (10 x 16.4 cm.) and view (14.7 x 17.2 cm.) on one sheet. From volume 3 of Valentijn’s Oud en nieuw Oost-Indien (Amsterdam, 1726). [Historic Maps Collection].

First printed view of Tasman’s New Zealand coastline and first printed European portrayal of Maori Indians. Formerly employed by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) as Minister to the East Indies, Valentijn probably had access to the cherished, and jealously guarded, VOC archives. The map shows Tasman’s ships approaching what he would called Murderers Bay, situated near Cook’s Strait. Not able to explore the area closely, Tasman assumed a continuous coastline. In the bottom view, Heemskerck and Zeehaen are shown off the Three Kings Islands, located northwest of the most northwestern point of New Zealand’s North Island, where the South Pacific and Tasman Sea converge. Giant Maoris appear on the hilltops. Arriving there on January 6 (1643), the Twelfth Night of the Epiphany, Tasman named them for the biblical three kings or wise men. Heavy surf and reefs prevented him from landing.

For more than a hundred years, until the period of Englishman James Cook’s first voyage (1768–1771), neither Tasmania nor New Zealand was visited further by European explorers.

Bowen, Emanuel, d. 1767. “A Complete Map of the Southern Continent: Survey’d by Capt. Abel Tasman & Depicted by Order of the East India Company in Halland [sic] in the Stadt House at Amsterdam.” Copperplate map, 37 × 48 cm. From John Harris’s Navigantium atque itinerantium bibliotheca . . . (London, 1744). Purchased with funds provided by the Friends of the Princeton University Library. Reference: Perry and Prescott, Guide to Maps of Australia 1744.01. [Historic Maps Collection]

First printed English map of Australia. Keeping the Dutch names, Bowen is quick to point out to the reader (in the top note) that only discovered territory is shown—hence all the blank spaces. Still, he claims that it “is impossible to conceive a Country that promises fairer from its Scituation, than this of Terra Australis; no longer incognita, as this Map demonstrates . . .” (bottom note). Below the Tropic of Capricorn, Tasman’s great discoveries of 1642 are sketched: Van Diemens Land and Nova Zeelandia; above it, his coastal exploration of northern Nova Hollandia, during which he missed finding the Torres Strait. In 1606, Spanish navigator Luis Vaez de Torres (fl. 1606) had stumbled on the strait now bearing his name on his way to Manila in the Philippines, but his report was kept secret by Spanish authorities—an example of the proprietary nature of European discovery during the Age of Exploration.