Pacific Winds

Learning the wind patterns of the Pacific Ocean was a major goal of early explorers. This would enable them to cross in both directions and not lose months of time caught in doldrums. (Ferdinand Magellan, for example, dawdled for three months traversing open Pacific water before he sighted land.) The Spanish navigator and Augustinian friar Andrés de Urdanetta (1498–1568) was the first to solve the puzzle of Pacific winds. As a teenager, he had crossed the Pacific on a Spanish voyage to the Spice Islands and spent a dozen years knocking around the western Pacific; later, he served in the viceroyalty of Mexico. By 1560, he had come to know the Pacific better than most men of his time and had developed a theory: winds move clockwise in the northern hemisphere, counterclockwise in the southern hemisphere.

Because of his knowledge and experience, Urdanetta was petitioned by King Philip II of Spain to help organize a fleet to conquer and colonize the Philippines. Though advanced in age and by then living the simple life of a monk, Urdanetta acceded to the king’s request and took the opportunity to test his wind theory. The expedition, commanded by Spanish nobleman Miguel López de Legaspi, sailed from the west coast of Mexico in November 1564 and reached Cebu, in the heart of the Philippines, in April 1565. Though they initially encountered hostility, the Spaniards were able, within weeks, to establish sovereignty over Cebu. Sent back to get reinforcements and relief for the new colony, Urdanetta departed for home in June by sailing north. Above latitude 35° N, he picked up the North Pacific westerlies he had theorized and, following a long clockwise arc, reached the coast of California in September and Acapulco, Mexico, in October. The friar was hailed as a hero and subsequently honored for his solution to the vexing issue of Pacific winds.

“Urdanetta’s route” became the main track for Spanish ships plying the Pacific for the rest of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—made even more famous by the annual Acapulco-Manila trips of the Spanish gold-carrying galleons.

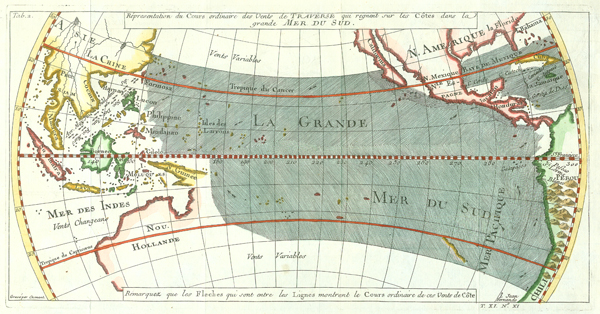

Jacques Nicolas Bellin, “Répresentation du cours ordinaire des vents de traverse qui regnent sur les côtes dans la grande Mer du Sud” (1753). Copperplate map, with added color, 15 × 29 cm. Probably issued in Abbé Prévost’s Histoire générale des voyages . . . (Paris, 1746–70). [Historic Maps Collection]

This popular map is an exact copy of William Dampier’s original, which he published with “A Discourse of Trade-Winds, Breezes, Storms, Tides, and Currents” in volume 2 of his Voyages and Descriptions (London, 1699). (For more on Dampier, see the Explorers section.) The map shows how winds aided ships sailing north along the west coast of South America and south along the coast of California. Dampier’s experiences in Southeast Asia in the 1680s taught him about the wind patterns shown here along the coasts of the continent.