Patagonian Giants

The myth of the Patagonian Giants, like other stories about remote, exotic places, captured the European imagination for a very long time. The first mention of this mythical race surfaced in the 1520s from the account of Antonio Pigafetta, chronicler of Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition:

But one day (without anyone expecting it) we saw a giant who was on the shore [near today’s Puerto San Julián, Argentina], quite naked, and who danced, leaped, and sang, and while he sang he threw sand and dust on his head. Our captain [Magellan] sent one of his men toward him, charging him to leap and sing like the other in order to reassure him and to show him friendship. Which he did. Immediately the man of the ship, dancing, led this giant to a small island where the captain awaited him. And when he was before us, he began to marvel and to be afraid, and he raised one finger upward, believing that we came from heaven. And he was so tall that the tallest of us only came up to his waist. Withal he was well proportioned. . . . The captain named the people of this sort Pathagoni.*

The etymology of the word is unclear, but Patagonia came to mean “Land of the Bigfeet.” Magellan seized two of the younger males as hostages to bring back to Spain, but they got sick and died on the journey.

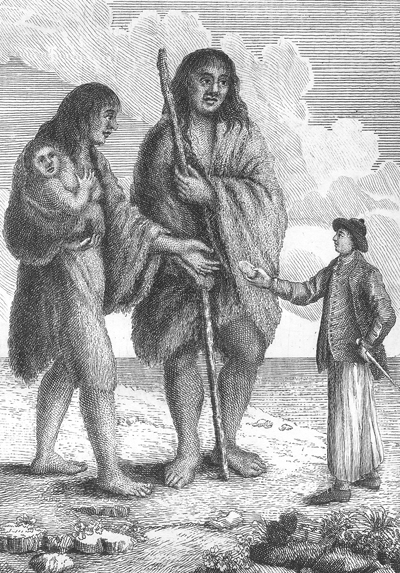

English sailor offering bread to a Patagonian woman giant. Frontispiece to Viaggio intorno al mondo fatto dalla nave Inglese il Delfino comandata dal caposqadra Byron (Florence, 1768), the first Italian edition of John Byron’s A Voyage Round the World in His Majesty’s Ship the Dolphin . . . (London, 1767) [Rare Books Division].

One hundred years later, in The World Encompassed (London, 1628), the first detailed account of Sir Francis Drake’s circumnavigation, the author, Drake’s nephew of the same name, wrote:

Magellane was not altogether deceived, in naming them Giants; for they generally differ from the common sort of men, both in stature, bignes, and strength of body, as also in the hideousnesse of their voice: but yet they are nothing so monstrous, or giantlike as they were reported; there being some English men, as tall, as the highest of any that we could see, but peradventure, the Spaniards did not thinke, that ever any English man would come thither, to reprove them; and thereupon might presume the more boldly to lie: the name Pentagones, Five cubits viz. 7. Foote and halfe, describing the full height (if not some what more) of the highest of them. But this is certaine, that the Spanish cruelties there used [referring to Magellan’s hostage taking], have made them more monstrous, in minde and manners, then they are in body; and more inhospitable, to deale with any strangers, that shall come thereafter.**

He reduced the height of the Patagonians from ten feet to seven and a half feet but was obviously more intent on discrediting the Spanish and blaming them for the “monstrosity” of the giants. Ironically, though, he was really confirming the basic facts behind the myth.

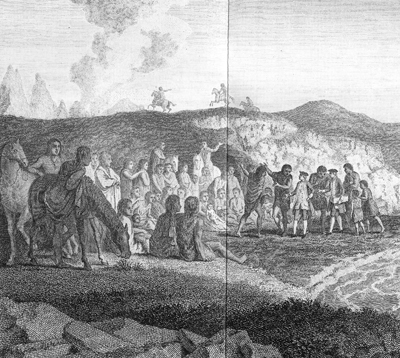

When we came within a little distance from the shore, we saw, as near as I can guess, about five hundred people, some on foot, but the greater part on horseback. . . . [O]ne of them, who afterwards appeared to be a Chief, came towards me: he was of a gigantic stature, and seemed to realize the tales of monsters in a human shape. . . . [I]f I may judge of his height by the proportion of his stature to my own, it could not be much less than seven feet. . . . Mr. Cumming [one of Byron’s officers] came up with the tobacco [a gift], and I could not but smile at his astonishment which I saw expressed in his countenance, upon perceiving himself, though six feet two inches high, become a pigmy among giants; for these people may indeed more properly be called giants than tall men . . . the shortest of whom were at least four inches taller.***

In all probability, these accounts were describing the Tehuelche Indians, native to the Patagonian area of Argentina, who are typically tall—but not monstrous giants.

Detail from “A Representation of the Interview between Commodore Byron and the Patagonians.” From volume 1 of John Hawkesworth’s An Account of the Voyages Undertaken by the Order of His Present Majesty for Making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere and Successively Performed by Commodore Byron, Captain Wallis, Captain Carteret, and Captain Cook . . . (London, 1773. [Rare Books Division].

*Antonio Pigafetta, Magellan’s Voyage: A Narrative Account of the First Circumnavigation, trans. R. A. Skelton (New Haven, Conn., 1969), 1:46–47, 50.

**Sir Francis Drake (nephew), The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake . . . (London, 1628), 28.

***John Hawkesworth, An Account of the Voyages Undertaken by the Order of His Present Majesty for Making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere and Successively Performed by Commodore Byron, Captain Wallis, Captain Carteret, and Captain Cook . . . (London, 1773), 27–28, 31–32.