Act I: The First Voyage

Expedition (1768–1771): One ship (Endeavour), 94 men

Charge (by the Royal Society and the British Admiralty): To view the transit of Venus from Tahiti and then to look for the Southern Continent

Accomplishments: Viewed the 1769 transit of Venus, discovered the Society Islands, made the first circumnavigation and charting of New Zealand, was the first European expedition to reach and chart the eastern shores of Australia

[Click on the images below for high resolution versions.]

From a scientific viewpoint, worldwide observations of the 1761 transit of Venus across the face of the Sun had been a failure. They had not been coordinated enough, and cloudy weather had been a problem in several viewing spots. Astronomers, hopeful in using the data to calculate the distance from Earth to the Sun and between the planets, urged the scientific community to take advantage of the next transit, which would occur on June 3, 1769; another one would not take place until 1874. Britain’s Royal Society’s committee, established to consider the organization’s participation, first met in November 1767, barely nineteen months before the event was due to take place. Among other things, it decided to send two observers to the Pacific Ocean and to ask the government to supply the necessary ship. Alexander Dalrymple (1737–1808), Scottish geographer and Society fellow—and a main proponent of the existence of a Southern Continent—was offered the role as first observer. He declined, however, when the British Admiralty refused to have a non-naval person command one of its vessels, which was Dalrymple’s condition.

Enter James Cook, who had just returned from surveying Newfoundland, had recently observed an astronomical event, and who had years of navigational and marine experience; moreover, he was a naval man who had the backing of Philip Stephens, secretary of the Admiralty, who admired Cook’s charting work and naval service, and Sir Hugh Palliser, governor of Newfoundland, a longtime Cook mentor and supporter. A merchant collier named Earl of Pembroke was purchased and refitted for the voyage, and renamed Endeavour.

Cook was promoted to lieutenant as commander of the expedition, and he received the Society’s affirmation in May 1768 to be their second Venus observer. (Charles Green, English astronomer and Society fellow, was the first.) Time was of the essence now. Captain Samuel Wallis had just returned from his circumnavigation with the discovery of an island (Tahiti) that would be a perfect site for the Venus observations. (For more on Wallis, see the Explorers section.) The Royal Society requested and received permission to send along, at his own expense, Joseph Banks (1743–1820), a renowned and wealthy English botanist and natural scientist, who, in turn, brought Daniel Solander (1733–1782), a Swedish botanist and British Museum librarian, the artist Sydney Parkinson (d. 1771), and a retinue of several personal servants and two greyhounds. Also aboard was a goat that already had circumnavigated the world with Wallis.

Portrait of Captain James Cook. Engraving by James Basire from a portrait by William Hodges. Frontispiece to Cook’s A Voyage towards the South Pole . . . (London, 1777). [Rare Books Division]

Book:

Hawkesworth, John. An Account of the Voyages Undertaken by the Order of His Present Majesty for Making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere and Successively Performed by Commodore Byron, Captain Wallis, Captain Carteret, and Captain Cook, in the Dolphin, the Swallow, and the Endeavor, Drawn Up from the Journals Which Were Kept by the Several Commanders, and from the Papers of Joseph Banks, Esq. 3 vols. 1st ed. London, 1773. Volumes 2 and 3 are devoted to Cook’s first voyage. [Rare Books Division]

An English writer and journalist, Hawkesworth was commissioned by the British Admiralty to edit for publication the narratives of its officers’ circumnavigations. He was given full access to the journals of the commanders and the freedom to adapt and re-tell them in the first person. Cook was already on his way back from his second Pacific voyage, temporarily docked at Cape Town (South Africa), when he first saw the published volumes: he was mortified and furious to find that Hawkesworth claimed in the introduction that Cook had seen and blessed (with slight corrections) the resulting manuscript. (In his defense, Hawkesworth also had been a victim of misunderstanding.) Cook had trouble recognizing himself. Moreover, the work was full of errors and commentary introduced by Hawkesworth and, in Cook’s view, too full of Banks, who had promoted himself and the publication. Still, the work was popular; the first edition sold out in several months.

His Majesty’s Bark Endeavour

Captain Cook’s Ship on His First Global Circumnavigation, 1768–1771

Launched in 1764 as the merchant collier Earl of Pembroke designed to carry coal, the ship was purchased in 1768 by the Royal Navy for £2,300, renamed Endeavour, and refitted for Cook’s expedition. Its flat bottom was well suited for sailing along coasts in shallow waters and allowed the boat to be beached for the loading and unloading of cargo and for basic repairs. The addition of a third internal deck provided cabins and storerooms for men and supplies, and the navy armed the ship with ten four-pounder cannons and twelve swivel guns. Endeavour was a “full-rigged ship,” meaning that it used square sails on three masts; it measured 106 feet long and 29 feet wide, weighed 368 tons, and carried ninety-four men.

After Cook’s voyage, Endeavour was refitted as a stores ship, made a few trips to the Falkland Islands, then was sold for commercial use and sailed under the new name of Lord Sandwich. In 1775, after extensive additional repairs, the ship was given to the Admiralty for transporting soldiers to fight the colonial militia in the American Revolution. To prevent a French fleet from attacking the British settlement at Narragansett, Rhode Island, in August 1778, the British commander ordered the scuttling of twenty surplus ships to blockade the bay—one of them was the Lord Sandwich. Though the site of the sunken ship’s remains was located in 2000, the Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project announced in 2006 that the wreck would not be raised.

With marines, scientists, and crew, Endeavour departed from Plymouth, England, on August 26, 1768. Cook’s “secret” additional orders, to be opened at sea, contained instructions to search for the Southern Continent after his observations at Tahiti were completed. (For more on this fabled landmass, see the Terra Australis box in the Pacific Ocean section.) The ship stopped at Madeira for more supplies, including three thousand gallons of wine, before proceeding across the Atlantic, reaching Rio de Janeiro in November. The Portuguese viceroy was suspicious of the ship’s scientific nature and would not allow anyone ashore. At night, Banks and his men surreptitiously landed and brought back large numbers of plants and specimens for examination, including what was later named the Bougainvillea after the French explorer. (See Bougainville in the Explorers section.)

Cook decided to take the route around Cape Horn, rather than dealing with the vicissitudes of the Strait of Magellan, to reach the Pacific. In mid-January, he anchored in what he called the Bay of Success, opposite Staten Island, in the Strait of Le Maire, where the crew traded with the Fuegians. Banks led an exploring party inland but was unprepared for a rapid change of weather that stranded the group overnight in heavy snow and bitter cold. Two of his servants died, but the greyhounds somehow survived. On January 21, 1769, the expedition continued in a southwesterly direction, sighting the 1,400-foot rock triangle of Cape Horn a few days later and, with great surprise, passing it with little danger. Cook fixed it at 55°59′ S, 68°13′ W, remarkably close to its real position of 55°58′ S, 67°16′ W. (He noted that Wallis’s Dolphin had taken three months to pass through the Strait of Magellan during the same part of the year.)

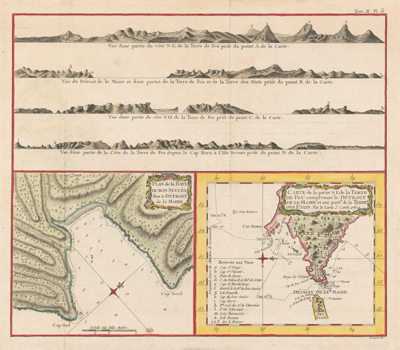

Bonne, Rigobert, 1727–1794. “Plan de la Baye du Bon Succès dans le Détroit de la Maire; Carte de la partie S.E. de la Terre de Feu comprenant le Détroit de la Maire et une partie de la Terre des Etats.” Two copperplate maps, with added color, 16 × 17 cm. and 14 × 16 cm., on sheet 31 × 35 cm. From Relation des voyages entrepris par ordre de Sa Majesté Britannique . . . (Paris, 1774), the French edition of John Hawkesworth’s An Account of the Voyages Undertaken by the Order of His Present Majesty . . . (London, 1773). Reference: Martinic, Cartografí́a magallánica, VIII, 341, 343. Shows Cook’s passage by Cape Horn and the Bay of Success, where Banks’s servants died. [Historic Maps Collection]

Inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego. [Hawkesworth, vol. 2, plate 1]

Upon the whole, these people appeared to be the most destitute and forlorn, as well as the most stupid of all human beings; the outcasts of Nature, who spent their lives in wandering about the dreary wastes, where two of our own people perished with cold in the midst of summer; with no dwelling but a wretched hovel of sticks and grass, which would admit not only the wind, but the snow and the rain; almost naked; and destitute of every convenience that is furnished by the rudest art, having no implement even to dress their food: yet they were content. [vol. 2, p. 59; emphasis added]

Matavai Bay (Tahiti) and Tahitian Boats. [Hawkesworth, vol. 2, plate 4]

We found the longitude of Port-Royal bay, in this island, as settled by Captain Wallis, who discovered it on the 9th of June 1767, to be within half a degree of the truth. We found Point Venus, the northern extremity of the island, and the eastern point of the bay, to lie in the longitude of 149°30′ this being the mean result of a great number of observations made upon the spot. Port-Royal bay, called by the natives Matavai, which is not inferior to any in Otaheite, may easily be known by a very high mountain in the middle of the island, which bears due south from Point Venus. . . . The low land that lies between the foot of the ridges and the sea, and some of the vallies, are the only parts of the island that are inhabited, and here it is populous; the houses do not form villages or towns, but are ranged along the whole border at the distance of about fifty yards from each other, with little plantations of plantains, the tree which furnishes them with cloth. . . . The canoe, or boats, which are used by the inhabitants of this and the neighbouring islands may be divided into two general classes; one of which they call Ivahahs, the other Pahies. The Ivahah is used for short excursions to sea, and is wall-sided and flat-bottomed; the Pahie for longer voyages, and is bow-sided and sharp-bottomed. The Ivahahs are all of the same figure, but of different sizes, and used for different purposes. . . . There is the fighting Ivahah, the fishing Ivahah, and the travelling Ivahah. . . . The Pahie is also of different sizes. . . . [vol. 2, pp. 184–85, 221–22]

The rest of the journey to Tahiti was fairly uneventful, Endeavour arriving in Matavai Bay on April 13 to a welcoming crowd of canoes. Knowing they would be there a long time, and having heard about the experiences of Wallis, John Gore (his third lieutenant, who had sailed with Wallis), and others, Cook drew up a list of rules for his men concerning their trading with and treatment of the islanders. (See the related box.) They established a Venus observatory fort at the isolated northern point of the bay. Generally, good relations with the Tahitians were maintained, but there were periodic clashes, usually about some theft of expedition supplies or equipment; some nails were removed from the ship’s hull for their iron. Venereal disease appeared to be rampant among the men, but it was really yaws, an endemic disease all over the Pacific, that was treated similarly with arsenic injections.

Cook’s Trading Rules for His Men at Tahiti RULES to be observe’d by every person in or belonging to His Majestys Bark the Endeavour, for the better establishing a regular and uniform Trade for Provisions &c with the Inhabitants of Georges Island 1st To endeavour by every fair means to cultivate a friendship with the Natives and to treat them with all imaginable humanity. 2d A proper person or persons will be appointed to trade with the Natives for all manner of Provisions, Fruit, and other productions of the earth; and no officer or Seaman, or other person belonging to the Ship, excepting such as are appointed, shall Trade or offer to Trade for any sort of Provisions, Fruit, or other productions of the earth unless they have my leave to do so. 3d Every person employ’d a Shore on any duty what soever is strictly to attend to the same, and if by neglect he looseth any of his Arms or woorking tools, or suffers them to be stole, the full Value thereof will be charg’d againest his pay according to the Custom of the Navy in such cases, and he shall receive such farther punishment as the nature of the offence may deserve. 4th The same penalty will be inflicted on every person who is found to imbezzle, trade or offer to trade with any part of the Ships Stores of what nature soever. |

June 3 dawned crystal clear, and for six hours, in temperatures rising to 119°F, the men did the best they could, but their astronomical observations of Venus were hindered by a dusky cloud surrounding the planet. For a week at the end of the month, Cook, with a small party, took the ship’s pinnace and circled the island so that he could chart it, a rather daring feat considering his vulnerability. Before leaving Tahiti on July 13, he had to deal with an attempted desertion by two crewmen and the kidnap and counterkidnap of Tahitian chiefs and British crew members to resolve this escalating problem. At the last moment, he reluctantly agreed to the addition of Tupaia, a young Tahitian priest and interpreter who wanted to join Banks’s party.

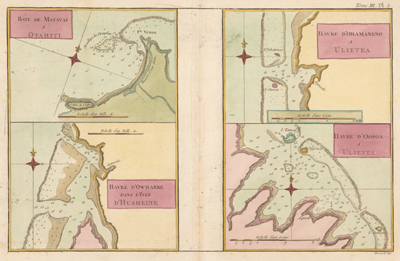

Bénard, Robert, fl. 1750–1785. “Baye de Matavai à Otahiti ; Havre d’Ohamaneno à Ulietea ; Havre d’Owharre dans l’isle d’Huaheine : Havre d’Oopoa à Ulietea.” Four copperplate maps on 1 sheet, with added color, 12 × 15 cm. or smaller, on sheet 27 × 40 cm. From Hawkesworth’s Relation des voyages entrepris par ordre de Sa Majesté Britannique . . . (Paris, 1774) [Historic Maps Collection]. Point Venus in Matavai Bay was the site of Cook’s observation of the transit of Venus in June 1769.

Breadfruit. [Hawkesworth, vol. 2, plate 3]

The bread-fruit grows on a tree that is about the size of a middling oak: its leaves are frequently a foot and a half long, of an oblong shape, deeply sinuated like those of a fig-tree, which they resemble in consistence and colour, and in the exuding of a white milkey juice upon being broken. The fruit is about the size and shape of a child’s head, and the surface is reticulated not much unlike a truffle: it is covered with a thin skin, and has a core about as big as the handle of a thin knife: the eatable part lies between the skin and the core; it is as white as snow, and somewhat of the consistence of new bread: it must be roasted before it is eaten. . . . [vol. 2, p. 80]

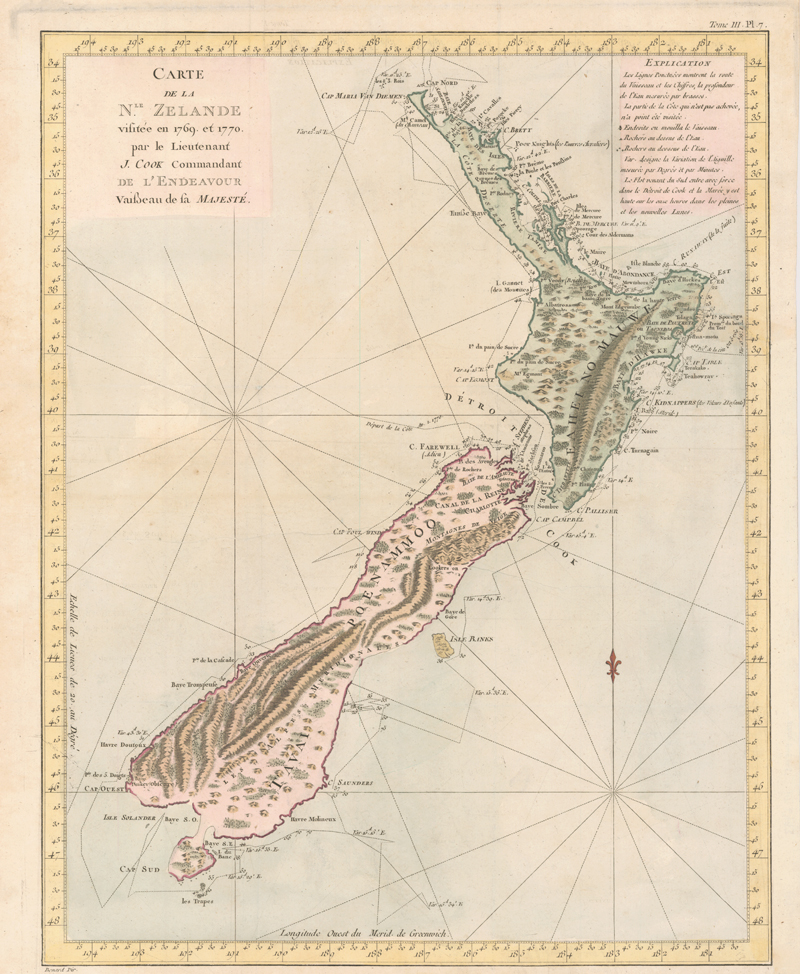

The Maori Indians they encountered were fierce fighters, and Cook’s attempts to make peace failed—even with Tupaia as translator—resulting in several shootings and deaths, which he deeply regretted. His surveying took him south, then back north, circling what proved to be the northern island in a counterclockwise direction; Endeavour endured some high seas with fearsome rollers. On January 22, 1770, from the top of an island (today’s Arapawa) in Queen Charlotte Sound, Cook realized that a strait separated New Zealand’s two islands; Banks named it Cook Strait in his honor. (During inland explorations here, the crew learned of the Maoris’ habit of cannibalizing enemies they killed). In a ceremony on another island-top in the sound, where a cairn was built and a post erected, Cook claimed both big islands for Great Britain.

By rounding the northern island’s southern cape and heading north along its eastern side, actually reaching within sight of their starting point (C. [Cape] Turnagain on the French New Zealand map), Cook proved his point without doubt: this was no Southern Continent. From there, his surveying work continued—this time in clockwise direction around the southern island, in the high 40°s and through difficult seas and wind, Banks still hoping this island might be a continent. The weather did not mellow, so Cook was unable to offer the frustrated Banks and his botanical party any time on land until they reached Cook Strait at the end of March and found anchorage on Stephens Island. After gathering wood, filling their water casks, and catching fish, there was no reason to delay their departure, which occurred on March 31, 1770, from Cape Farewell (appropriately called Adieu on the French map). Cook had decided to return home via the west in order to avoid Cape Horn’s notorious winter and to add opportunities for further exploration.

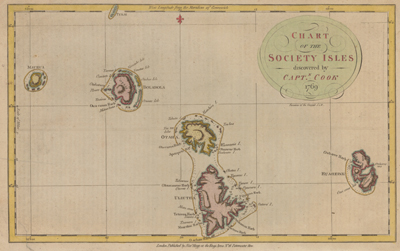

Hogg, Alexander, fl. 1778–1819. “Chart of the Society Isles Discovered by Captn. Cook, 1769.” Copperplate map, with added color, 22 × 34 cm. From G. W. Anderson’s A New, Authentic and Complete Collection of Voyages Around the World, Undertaken and Performed by Royal Authority . . . (London, 1784). [Historic Maps Collection]

New Zealander Tattoos. [Hawkesworth, vol. 3, plate 13]

The bodies of both sexes are marked with black stains called Amoco, by the same method that is used at Otaheite, and called Tattowing; but the men are more marked, and the women less. . . . [T]he men, on the contrary, seem to add something every year to the ornaments of the last, so that some of them, who appeared to be of an advanced age, were almost covered from head to foot. Besides the Amoco, the have marks impressed by a method unknown to us, of a very extraordinary kind: they are furrows of about a line deep, and a line broad, such as appear on the bark of a tree which has been cut through . . . and being perfectly black, they make a most frightful appearance. . . . [W]e could not but admire the dexterity and art with which they were impressed. The marks upon the face in general are spirals, which are drawn with great nicety, and even elegance, those on one side exactly corresponding with those on the other. . . . [N]o two were, upon a close examination, found to be alike. [vol. 3, pp. 452–53]

“Carte de la Nle. Zelande visitée en 1769 et 1770 par le Lieutenant J. Cook Commandant de l’Endeavour, vaisseau de sa Majesté.” Copperplate map, with added color, 46 × 36 cm. From John Hawkesworth’s Relation des voyages entrepris par ordre de Sa Majesté Britannique . . . (Paris, 1774). French copy of Cook’s foundation map of New Zealand, showing the track of the Endeavour around both islands, from October 6, 1769, to April 1, 1770. [Historic Maps Collection]

Endeavour came within sight of land on April 19, well north of the area charted by Tasman 125 years earlier. The New Holland (Australia) coast was exasperating, however, and Cook could not find a safe place to land until the afternoon of Saturday, April 28, when they entered Botany Bay (part of today’s Sydney Harbor), which Cook later named for the wide variety of plant life found there. The Aborigines that they saw there were unintelligible to Tupaia and kept away, avoiding contact. Through May and into June, Endeavour sailed north, arcing northwest, following the Great Barrier Reef coastline. On the evening of June 10, when most of the men were sleeping, the ship struck coral, stuck fast, and began leaking. Quick thinking and decisive action by Cook and his men—pumping furiously and jettisoning fifty tons of decayed stores, stone ballast, and cannons—kept the ship afloat and allowed a temporary underwater repair. A few days later, the damaged ship was safely beached on a barren shore (near today’s Cooktown, by the EndeavourRiver), and a fury of activity began more permanent work: the expedition had avoided a real disaster. (Henceforth, the British Admiralty would send Cook out with two ships for safety.) During this time, the men enjoyed more favorable interactions with the natives, but not without miscommunications and incidents of distrust. (See the box on Cook’s ultimately positive views on the New Hollanders.) By August 13, the ship was ready to resume its journey.

The labyrinth of treacherous islands and reefs was threaded slowly and carefully, with vigilance and some luck, as the expedition sailed northward through the Great Barrier Reef, westward around the northernmost point of New Holland, and into what Cook called Endeavour Strait. He stopped briefly at Possession Island (his name) where, now knowing he was in territory explored by the Dutch, he claimed the whole coastline he had just charted for King George III. It was a proud moment, essentially marking the end of Cook’s first Pacific voyage’s geographical discoveries.

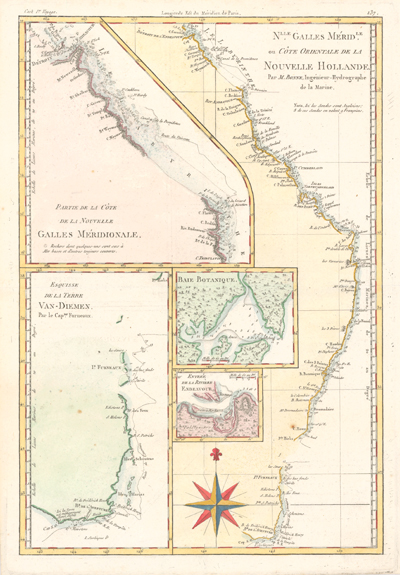

Bonne, Rigobert, 1727–1794. “Nlle. Galles Mérid.le [i.e. Nouvelle Galles Méridionale], ou, Côte orientale de la Nouvelle Hollande.” Copperplate map, with added color, 34 × 17 cm. Plate 137 from vol. 2 of R. Bonne and N. Desmarest’s Atlas Encyclopédique . . . (Paris, 1788). [Historic Maps Collection]

Places to note include Botany Bay (B. de Bontanique) around 34°, part of today’s Sydney, highlighted in an inset, and Endeavour River (Riv. Endeavour) at the top, between 15° and 16°, where the ship was repaired. The large inset at the bottom left shows the part of Tasmania explored by Captain Tobias Furneaux of the Adventure during Cook’s second voyage.

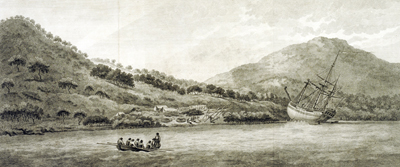

Beached Endeavour and Examination of Its Damage. [Hawkesworth, vol. 3, plate 19]

In the morning of Monday the 18th [June 1770], a stage was made from the ship to the shore, which was so bold that she floated at twenty feet distance: two tents were also set up, one for the sick, and the other for stores and provisions, which were landed in the course of the day. We also landed all the empty water casks, and part of the stores. . . . At two o’clock in the morning of the 22d, the tide left her, and gave us an opportunity to examine the leak, which we found to be at her floor heads, a little before the starboard fore-chains. In this place the rocks had made their way through four planks, and even into the timbers; three more planks were much damaged, and the appearances of these breaches was very extraordinary: there was not a splinter to be seen, but all was as smooth, as if the whole had been cut away by an instrument: the timbers in this place were happily very close, and if they had not, it would have been absolutely impossible to have saved the ship. But after all, her preservation depended upon a circumstance still more remarkable: in one of the holes, which was big enough to have sunk us, if we had eight pumps instead of four, and been able to keep them incessantly going, was in great measure plugged up by a fragment of the rock, which, after having made the wound, was left sticking in it. . . . By nine o’clock in the morning the carpenters got to work upon her, while the smiths were busy in making bolts and nails. [vol. 3, pp. 557, 559–60]

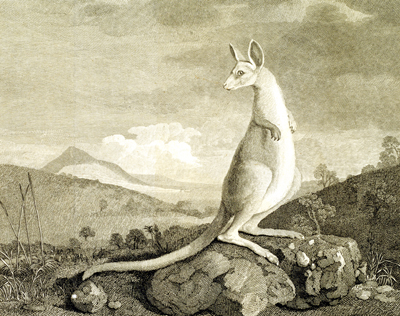

Kangaroo. [Hawkesworth, vol. 3, plate 20]

As I was walking this morning at a little distance from the one ship, I saw myself one of the animals which had been so often described: it was of a light mouse colour, and in size and shape very much resembling a greyhound; it had a long tail also, which it carried like a greyhound; and I should have taken it for a wild dog, if instead of running, it had not leapt like a hare or deer: its legs were said to be very slender, and the print of its foot to be like that of a goat. . . . [vol. 3, p. 561]

Natives of New Holland

From what I have said of the Natives of New-Holland they may appear to some to be the most wretched people upon Earth, but in reality they are far more happier than we Europeans; being wholly unacquainted not only with the superfluous but the necessary Conveniences so much sought after in Europe, they are happy in not knowing the use of them. They live in a Tranquillity which is not disturb’d by the Inequality of Condition: The Earth and sea of their own accord furnishes them with all things necessary for life, they covet not Magnificent Houses, Household-stuff &c., they live in a warm and fine Climate and enjoy a very wholesome Air. . . . In short they seem’d to set no Value upon any thing we gave them, nor would they ever part with any thing of their own for any one article we could offer them; this in my opinion argues that they think themselves provided with all the necessarys of Life and that they have no superfluities. [Journals, p. 174]

In Batavia (today’s Jakarta, Indonesia), where Endeavour anchored on October 7, 1770, there was English news! American colonists had refused to pay taxes, and the king had dispatched troops to put down the first signs of a rebellion. Because of Cook’s strict insistence on a clean ship, exercise, and a healthy diet (including scurvy-preventing sauerkraut) for his crew, he had, until then, lost no man to sickness. Now, in one of the most diseased foreign cities, malaria, dysentery, and other ills began their work: almost everyone got sick during the months they remained on the island for refit and repair, and many died, including the Tahitian, Tupaia. Even after Cook left for home (December 26), the unfortunate deaths continued—thirty-four in all by the time they reached Cape Town in March—and five more would die there or on the last leg back to England. (Never failing to provide milk for the officers, Wallis’s goat was among the elite, having survived its second circumnavigation.) Endeavour docked in the Downs on July 12, 1771.

The three men—Cook, Banks, and Solander—companions during more than a thousand days at sea, now shared a seven-hour post-chaise trip through Kent to London—riding into history. The botanists had brought back a wealth of scientific data about plant and animal species, including thousands of plants never seen in England as well as the amazing drawings of Sydney Parkinson and Alexander Buchan, the expedition’s artists, who had both died on the voyage. Cook had recorded his observations of the life and customs of the Polynesians of Tahiti, the Maori of New Zealand, and the Aborigines of Australia. And he had his accurate charts, which would immediately improve the mapping of the Pacific Ocean.

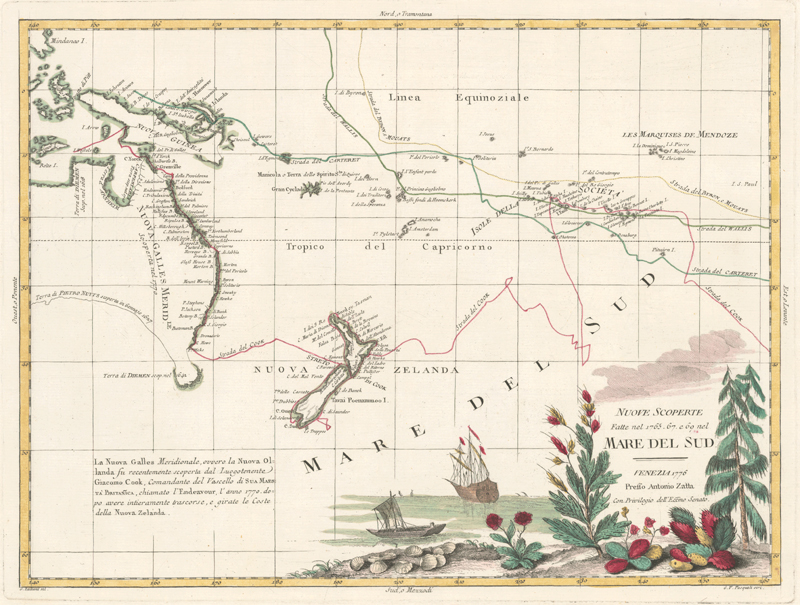

Zatta, Antonio, fl. 1757–1797. “Nuove scoperte fatte nel 1765, 67, e 69 nel Mare del Sud” (1776). Copperplate map, with added color, 29 × 39 cm. From Zatta’s Atlante novissimo (Venice, 1775–1785). Reference: Perry and Prescott, Guide to Maps of Australia, 1776.01. [Historic Maps Collection]

First decorative map to show Cook’s tracks in the Pacific, recording the discoveries he made in Australia, New Zealand, New Guinea, and the South Pacific during the Endeavour voyage. Also noted are the tracks of Philip Carteret, John Byron, and Samuel Wallis. The chartings of the east coast of Australia and New Zealand’s two islands are shown in detail, drawn from Cook’s own map of the region, “Chart of Part of the South Seas” (1773). The ship depicted is most probably the Endeavour.