Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, 1729–1811

Expedition (1766–1769): Two ships (Boudeuse and Etoile), 330 men

Charge (by King Louis XV of France): To transfer French settlements in the Falklands to the Spanish, then to proceed to the East Indies by crossing the Pacific, taking possession of any new or empty land, and to seek an island near China for a trading post for the French East India Company

Accomplishments: First French circumnavigation of the world, some island discoveries in the Tuamotu Archipelago, carried the first woman (Jeanne Baré) to circle the world

Legacy of Bougainville’s name: Bougainvillea (plant), Bougainville (largest of the Solomon Islands), Bougainville Strait

[Click on the images below for high resolution versions.]

Portrait of Louis-Antoine de Bougainville. From vol. 1 of Jules-Sébastien-César Dumont d’Urville’s Voyage pittoresque autour du monde . . . (Paris, 1834-1835). [Rare Books Division]

Born in Paris during the Age of Enlightenment, Bougainville enjoyed the advantages of an upper-middle-class life: a boarding school education, access to aristocratic salons, influential acquaintances through his father’s elected position in Paris’s municipal council. Deciding against following his father into a legal career, Bougainville entered the army in 1753. In London, on a diplomatic appointment, he published two volumes on integral calculus, for which he was elected to the Royal Society, Britain’s prestigious scientific organization. Later, he participated in the French defense of Quebec when it was besieged by the British and fell in September 1759. (Coincidentally, James Cook, then only a ship’s master, had supplied the British Navy with more accurate maps of the St. Lawrence River in that area, allowing General Wolfe safer amphibious access to the city.) On returning to France at the end of 1760, Bougainville embarked on a plan to colonize the Falkland Islands. But the settlement there that he established and helped finance in 1763 irked Spain and Great Britain, who already had claims on the islands; as a result, in December 1766, Bougainville was sent back to transfer ownership to Spain. From the Falklands, he continued westward on a circumnavigation of the world.

French King Louis XV supported Bougainville’s expedition, for its success would add prestige to a country still absorbing its defeats in the Seven Years’ War (1754–1763)—the North American part is usually referred to as the French and Indian War—including the loss of much of its colonial territory in the New World. Bougainville commanded the frigate Boudeuse; the Etoile joined him in Rio de Janeiro in June 1767. After negotiating the sale of the Spanish takeover of the Falklands, Bougainville sailed into the Strait of Magellan but needed fifty-two days to complete the transit, owing to rough seas and winds. He found evidence of a prior passage by the British ships commanded by Samuel Wallis and Philip Carteret. (For more on their voyages, see Wallis/Carteret in the Explorers section.) The hard lives of the inhabitants of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego that he observed both impressed and distressed him. Bits of glass given as a present to a child were innocently ingested (with expected dire results), causing the natives to distrust the French.

Books:

- Bougainville, Louis-Antoine de, comte, 1729–1811. Voyage autour du monde: Par la frégate du roi La Boudeuse, et la flûte L’Étoile: en 1776, 1767, 1768, & 1769. Paris, 1771. First French edition. [Rare Books Division]

Though favorably reviewed, Bougainville’s account of his voyage was not a runaway best-seller. The first edition consisted probably of only a thousand copies; the second edition, in two volumes, was published the next year, as was the first English edition, in a translation by J. R. Forster. But the book continued to stay in print—in abridged versions, new impressions, additional translations—into the twentieth century.

- Taitbout, d. 1799. Essai sur l’isle d’Otahiti, située dans la mer du Sud; et sur l’esprit et les mœurs de ses habitans. Avignon and Paris, 1779. [Rare Books Division]

The first extensive work specifically on Tahiti. After its successive discoveries by Wallis, Bougainville, and Cook, Tahiti came to symbolize a living social and political experiment in the minds of many European philosophers: a primitive paradise that became spoiled and tainted by Western decadence. In this little work, often attributed to Bougainville—perhaps because it borrows extensively from his narrative and the earlier accounts of Cook and his accompanying naturalists, Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander—Taitbout speculates on the fundamental differences between the “homme sauvage” and the “homme civilize,” drawing from the example of Tahiti. He suggests that societies like Tahiti, that evolved in isolation, could offer political lessons to European nations, but acknowledges that the arrival of Europeans on their shores will deal them a death blow. Taitbout’s purpose, in his own words (translated), is revolutionary: “to assist in bringing about the much-desired general revolution, to which the human spirit will one day owe the free, complete, and perfect union of all men.”

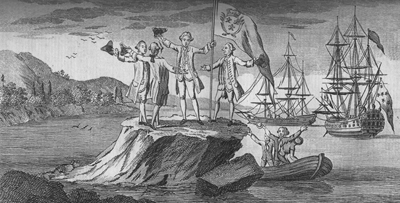

“Monsieur Bougainville Hoisting the French Colours on a Small Rock Near Cape Forward in the Streights of Magellan.” From vol. 4 of David Henry’s An Historical Account of All the Voyages Round the World, Performed by English Navigators . . . (London, 1773). [Cotsen Collection]

Mons. Bougainville and his party landed on a small rock, which barely afforded room for four persons to stand on, and here they hoisted the colours of the boat, and repeatedly shouted Vive le Roi. . . . A Striking instance of the vanity by which the French nation is distinguished! [vol. 4, p. 194]

Upon entering the Pacific Ocean, strong southeasterly winds forced Bougainville to abandon plans to seek Juan Fernández Island; instead, the expedition headed north to the Tropic of Capricorn, then west. Unable to land on any of the Tuamotu Islands because of threatening reefs, Bougainville called them the Dangerous Archipelago. In early April they encountered Tahiti, and after seeking a port for several days finally moored on April 6, 1768, less than a year after Wallis had arrived.

Out walking in the interior parts of the island, Bougainville thought he was transported into the Garden of Eden: everywhere he found hospitality, people at ease, bountiful fruit trees, a refreshing climate. (However, there were some shootings and deaths, but these incidents created, it seemed, only temporary conflicts.) He claimed the island for France, naming it New Cythera after the Greek island where, according to the classical myth, Aphrodite (Venus), the goddess of love, had arisen full-born from the sea. His glowing reports of the island, echoing Wallis’s, would add credence, in the minds of European philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, to the idea of the noble savage who lives in a state of nature, unencumbered by civilization and divine revelation.

After nine days, and the loss of six anchors because of his poor anchorage, Bougainville took advantage of the easterly winds and departed. A friend of the chief, named Ahutoru, accompanied the expedition. (On his arrival in France, Ahutoru was introduced to the royal court and Parisian lifestyle; he stayed in the country for more than a year, enjoying such new experiences as opera, shopping, and entertaining. In 1771, on his way back to Tahiti, Ahutoru caught smallpox and died in Madagascar.) During the stay on Tahiti, the true gender of the valet of Bougainville’s botanist, Philibert Commerçon, was revealed to the crew: “he” was a woman, Jeanne Baré—in fact, she was his mistress. (Commerçon had discovered the bougainvillea in Brazil earlier in the trip.) It also appeared that a number of Bougainville’s men had contracted syphilis, suggesting that Wallis’s crew had brought venereal disease to the island.

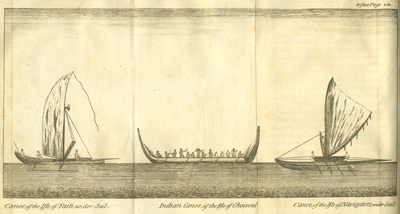

Illustration of three different Pacific “canoe” styles observed by Bougainville: at Tahiti, Choiseul (one of the Solomon Islands), and Navigators Islands (Samoa). From Bougainville’s A Voyage Round the World . . . (Dublin, 1772). [Rare Books Division]

Over the course of twenty-eight months, Bougainville had lost fewer than a dozen men, a real credit to his leadership and marine abilities. Both ships had survived. More important, in one successful voyage, he had jettisoned France into the forefront of Pacific naval exploration, despite failing to claim any land near China. Bougainville continued to serve France in naval operations against the British in the American Revolution; he barely escaped the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution and was made a count of the empire by Napoleon I in 1808. Bougainville died in Paris in 1811.

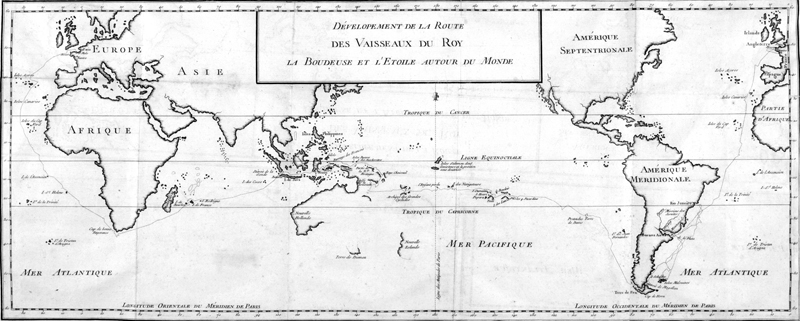

“Dévelopement de la route des vaissaux du roy La Boudeuse et L’Étoile autour du monde.” From Bougainville’s Voyage autour du monde . . . (Paris, 1771). [Rare Books Division]

Bougainville’s route around the world. A note accompanying the mid-ocean placement of the Solomon Islands states that both their existence and location are in doubt. The map’s longitude is measured from Paris, France, emphasizing the national nature of mapmaking at this time. (Greenwich, England, was not internationally adopted as the prime meridian until 1884.)