|

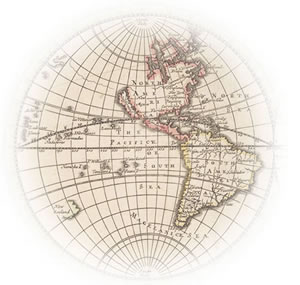

This collection of early printed maps of the world offers snapshots of a world that was largely unknown at the time many of the maps were made. For most people, then, familiar territory encompassed not much more than a neighborhood. Travelers were few, and even sailors crept along the coastlines. Nevertheless, scholars and visionaries had long looked beyond the horizon in hope of grasping the measure of the Earth and its place in the universe. The maps in this collection mark the European rediscovery of classical Greco-Roman culture— that enormous expansion of literacy and knowledge known as the Renaissance. This development of technique was parallel by the development of scientific knowledge: astrology became astronomy; mathematics led to physics, and maps pictured the progression. Three major strands of thought—classical Greek geography, medieval religious representations of the world, and the effects of new scientific concepts and information from the early voyages of discovery—appear alone or in combination on printed maps for more than two hundred years. As records, maps were not systematic; sometimes it took many years for a scientific discovery to be reflected in the maps and as long for outmoded notions to disappear from them. By the end of the seventeenth century, however, the world had become more thoroughly explored and understood. The pioneering work of such seventeenth-century scientists as Copernicus, Kepler, and Halley had settled almost all the important questions in the fields of astronomy and mathematics. Many of the basic concepts and techniques that were so successfully developed and applied to maps and mapmaking by 1700 continue in practice to this day. |