Monomotapa

Mwene Mutapa, or Monomotapa, was the title borne by a line of kings ruling an African territory between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers, in what is now Zimbabwe and Mozambique, from the 14th to the 17th century. Their domain was often called the empire of the Mwene Matapa, or simply Matapa (or Mutapa). Today, it is associated with the World Heritage historical site known as the Great Zimbabwe Ruins, the largest ancient stone construction south of the Sahara, located in the southeastern part of modern Zimbabwe. When the Portuguese first came upon these vast ruins in the early 1500s, they thought they had found the fabled capital of the Queen of Sheba. In further expeditions, the Portuguese gained control of the country during the first half of the 17th century, but were expelled by tribal warriors after a disastrous defeat in 1693. Monomotapa was rumored to be an area of untold wealth in gold—in fact, the high plateau area does have rich deposits—which probably accounts for the prominence of the name on early European maps of Africa.

1541

1541 map

Waldseemüller, Martin, 1470-1521?

“Tabula noua partis Africæ.” Woodcut map, with added color, 29 x 40 cm. Lorenz Fries’ reduced version of Waldseemüller’s map, from Ptolemy’s Geographia (Lyon, 1541). [Historic Maps Collection]

An imaginative, and decorative, revision of Waldseemüller’s 1513 map, which was the first separately printed map of southern Africa. Waldseemüller was the most influential geographer of the early 16th century, famous as the man who named “America.” His 1513 edition of Ptolemy, produced with two Alsace-Lorraine friends, included an additional twenty “modern” maps and is thus regarded as the first modern Ptolemy atlas. Better known as a writer on medical topics, Fries seems to have worked from about 1520 to 1525 as an editor on the cartographic corpus created by Waldseemüller.

Fries’ rendering introduces a number of embellishments. The coastline is full of names given by the Portuguese, but what was Waldseemüller’s empty interior is now occupied by anonymous mountains, a lake, Sapha (from which three rivers radiate), three seated rulers, an elephant, a cockatrice, and two snakes. The cockatrice (or basilisk), depicted here as a giant rooster with a lizard-like tail, was a legendary creature able to turn people into stone with its glance, its touch, or its breath. The Latin text adjacent to the creature states that basilisks live under the mountains in this part of Africa and because of them the area is like a desert. Although today’s Kalahari Desert is in that general area (but further south), the placement is coincidental; most likely Fries misinterpreted ideas associated with the Sahara region in the north. He also ignores earlier references to a Sacaff or Saaph lake that relate it to the Nile and put it in Abyssinia (Ethiopia). He does show the Mountains of the Moon (Mone Lune) as the source of the Nile.

In the lower right corner, the king of Portugal (Emanuelis Regis), bearing the royal banner of Portugal and a scepter, rides a bridled sea monster. Reigning from 1495 to 1521, Manuel I (“the Fortunate”) occupied the throne during the great expansion of Portugal’s mercantile empire. It was during his reign that Vasco da Gama discovered the route to India—toward which the figure on the map heads.

1561

1561 map

Ruscelli, Giralamo, d. ca. 1565.

“Africa nuova tavola.” Copperplate map, with added color, 17 x 24 cm. From Ruscelli’s La geografia di Claudio Tolomeo, Alessandrino . . . (Venice, 1561). [Historic Maps Collection]

In his map of southern Africa, the Venetian editor and cartographer Ruscelli removes all symbols and figures and returns to a simple depiction of the geography of the land. The Mountains of the Moon (Monti de Luna) are centrally placed in southern Africa, and the Nile is born from the outflow of three lakes situated at their base. A number of coastal rivers are identified. Madagascar bears its earlier name, Island of San Lorenzo (Isola de S. Lorenzo), given by Diogo Dias, the Portuguese navigator who first landed there in 1500 on the feast day (August 10) of St. Lawrence. The stippled ocean and pimply mountain ranges reflect the Italian copperplate style of engraving of the period.

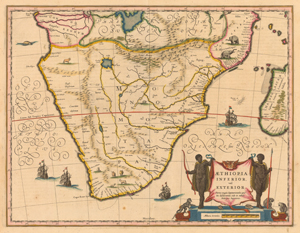

1635

1635 map

Blaeu, Willem Janszoon, 1571-1638.

“Aethiopia inferior, vel exterior.” Copperplate map, with added color, 37 x 48 cm. From Blaeu’s Theatrum orbis terrarum, sive atlas novus (Amsterdam, 1635). [Historic Maps Collection]

The standard map of southern Africa throughout the 17th century. This fine exemplar of the Dutch “golden age” from the Blaeu family firm predates the Dutch settlement of Cape Town by seventeen years. The cartouche shows two Africans holding up an ox hide displaying the title, with monkeys and turtles at the bottom. In this map, the Mountains of the Moon (Lunae Montes) form the northern boundary of a vast region named Monomotapa.

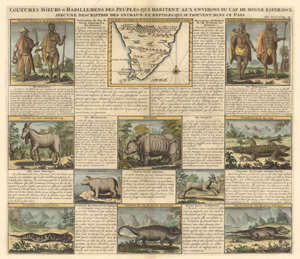

1719

1719 map

Chatelain, Henri Abraham, 1684-1743.

“Coutumes moeurs &c habillemens des peuples qui habitent aux environs du Cap de Bonne Esperance avec une description des animaux et reptiles qui se trouvent dans ce pais.” Copperplate map, with added color, 10 x 12 cm., set among ten other images and accompanying blocks of text on a 38 x 44 cm. sheet. From Chatelain’s Atlas historique, ou, Nouvelle introduction à l’histoire, à la chronologie & à la géographie ancienne & moderne…(Amsterdam, 1705-1720). [Historic Maps Collection]

Chatelain is admired for his seven-volume masterwork on the history, chronology, and geography of the world, with text by Nicolas Gueudeville and over three hundred engravings, many of them large foldouts. In this decorative sheet from that work, he introduces some of the peoples and animals that inhabit southern Africa, drawing upon contemporary Dutch discoveries. His little map, however, borrows from one published in Paris more than thirty years earlier—so there is no cartographic advance here. Hottentots and Namaquas, shown in typical dress, are the two major groups that the Europeans have encountered. According to the text, the natives’ manners and habits are as different from those of Europeans as that part of the world is distant from Europe. While natives around the Cape of Good Hope do not believe in the Creation or the Redemption, they display more charity and fidelity than is often found among Christians, and they are jealous of their freedom to the point of excess. Hottentots are willing to serve the Dutch to obtain bread and tobacco, but they think the Dutch are enslaved to the earth and have to seek safety in their homes and forts; they themselves feel secure to range anywhere they please. The Hottentots have personal integrity and will share what they have with strangers; the Dutch trust them in their homes.

Among the animals pictured and described are the zebra, the rhinoceros, and the hippopotamus (vache marine). One unusual reptile found at the Cape is a lizard with three white crosses on its back. Its bite is not as bad, apparently, as that of the grand lezard, but there is a horned viper whose venom is extraordinarily dangerous.

1804

1804 map

Reinecke, I. C. M. (Johann Christoph Matthias), ca. 1770-1818.

“Charte der Südspitze Africa’s und der Colonie vom Vorgebirge der guten Hoffnung hauptsächlich nach Barrow’s neuesten Reisen entworfen . . .” (Weimar, 1804). Copperplate map, with added outline color, 38 x 58 cm. [Historic Maps Collection]

Reinecke was the official cartographer to the Geographical Institute in Weimar, which produced some of the finest world atlases in Germany during the 19th century. On this map, he has outlined in yellow the boundary of the Cape Colony and its several districts. As indicated in the title, it is chiefly based on the 1797-1798 travels of Sir John Barrow, who published his two-volume account in London between 1801 and 1804; hence, the map contains information that was as up-to-date as possible. Accompanying Lord Macartney, who had been sent to Cape Town in 1797 as the first governor of Britain’s new colony, Barrow traveled extensively into the interior. His task was to reconcile disputes among the Boers, Hottentots, and Kaffers, who were each striving to graze and hunt over the same territory, and to map the troubled area. (Not surprisingly, Barrow suggested that each group have it own exclusive area, an early form of apartheid.)

Utilizing the standard method of travel—a covered wagon pulled by a team of ten or twelve oxen—Barrow’s group made treks east across Karro Land (arid desert) to the Graaf Reynett district, into the country of the Kaffers, then along the coast back to Cape Town. Next, he went north to the land of the Namaquas and circled back. His personal equipment included a small pocket sextant, an artificial horizon (useful for determining latitude), a pocket compass, a small telescope, a case of mathematical instruments, and a rifle. In 1804, Barrow was appointed Second Secretary to the Admiralty, a position from which, over the next forty years, he effectively supported and encouraged British exploration, particularly in West Africa and the Arctic.

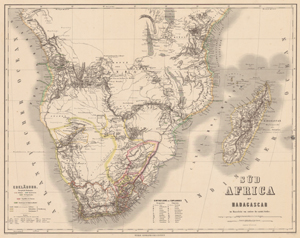

1860s

1860s map

Kiepert, Heinrich, 1818-1899.

“Süd Africa mit Madagascar.” Steel engraved map, with added outline color, 48 x 63 cm. From Kiepert’s Hand-Atlas der Erde und des Himmels, in siebzig Blättern (Weimar, 186?). [Historic Maps Collection]

A later, richer map published by the Geographical Institute in Weimar. Kiepert, who headed the Institute for a number of years, was a professor of geography at the University of Berlin and an expert on ancient historical cartography. Although he was especially interested in Asia Minor, he also compiled a large number of special and educational maps on other areas. This atlas map of South Africa, edited by Adolf Gräf, shows the routes of some of the major European explorers through 1860, ranging as far north as the equator. The Orange Free State and the Transvaal Republic, two Boer states recognized by the British as independent countries in the 1850s, are circumscribed in pink.

Madagascar and surrounding islands are accurately sited, and the coastlines are markedly improved, building on the extensive surveying efforts of Captain W. F. W. Owen and his crews aboard HMS Leven and HMS Barracouta in the 1820s. They produced several hundred charts that became the standard for most of the 19th century. The early travels (1849-1856) of Livingstone, including his transcontinental route along the Zambezi River and overland to S. Paulo de Loanda on the Atlantic Ocean, accounts for much of the detail across the center of this map. Also clearly represented are the discoveries (1857-1859) of Burton and Speke in the central lake region on the eastern side of the continent.