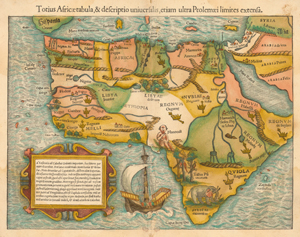

1554

1554 map

Münster, Sebastian, 1489-1552.

“Totius Africæ tabula, & descriptio uniuersalis, etiam ultra Ptolemæi limites extensa.” Woodcut map, with added color, 26 x 35 cm. From Münster’s Cosmographia uniuersalis (Basel, 1554). [Historic Maps Collection]

The earliest obtainable map of the whole continent of Africa. Because it was issued with some variations in both of Münster’s very popular works, Geographia (1540-1552) and Cosmographia (1544-1628), the map is difficult to date precisely. Münster was a professor of Hebrew at Heidelberg and then at Basel, where he settled in 1529 and later died of the plague. By soliciting descriptions and maps from German scholars and foreigners, he was able over time to include up-to-date information in the various editions of his atlases, becoming the most influential cartographer of the mid-16th century. Münster was the first mapmaker to print separate maps of the four then known continents (Europe, Africa, Asia, America).

The map of Africa contains many interesting—if not curious— features: a one-eyed giant seated over Nigeria and Cameroon, representing the mythical tribe of the “Monoculi”; a dense forest located in today’s Sahara Desert; and an elephant filling southern Africa. The Niger River begins and ends in lakes. The source of the Nile lies in two lakes fed by waters from the fabled Mountains of the Moon, graphically presented as small brown mounds. Several kingdoms are noted, including that of the legendary Prester John [see Ortelius’s “Presbiteri Johannis” map in the “Central Africa” section for further discussion of him], as well as “Meroë,” the mythical tombs of the Nubian kings. Few coastal towns are noted, and there is no Madagascar yet. A simplified caravel, similar to those used by the Portuguese (and Columbus), sails off the southern coast. One of the intriguing aspects of this map is the loop of the Senegal River, which is shown entering the ocean in today’s Gulf of Guinea. Actually, this is the true route of the Niger River, but that fact will not be confirmed until the Lander brothers’ expedition in 1830. Strangely, this loop disappeared from subsequent maps of Africa for the next two hundred years.

The text in the large cartouche offers a rudimentary itinerary for sailors from Lusitania to Calechut (Calicut, India), describing a route which essentially avoids Africa. Lusitania was a province of the Roman Empire, comprising most of modern Portugal and part of Spain.

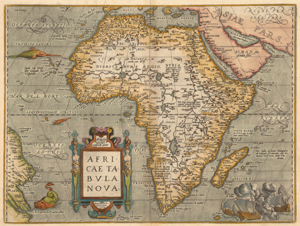

1584

1584 map

Ortelius, Abraham,1527-1598.

“Africae tabula noua.” Copperplate map, with added color, 37 x 49 cm. From Ortelius’s Theatrum orbis terrarum (Antwerp, 1584). [Historic Maps Collection]

The standard map of Africa for the last quarter of the sixteenth century. Ortelius lived and died in Antwerp, where he had a bookselling business. He traveled to many of the great book fairs, established contacts with literati in many countries, collected maps, and became an authority on historical cartography. In 1570, he published the Theatrum, an atlas of fifty-three maps, the first collection of uniform-sized maps depicting all the countries of the known world—the first real atlas. Each map had text on the back describing the country depicted and listing Ortelius’s sources of information. The atlas was phenomenally successful and revered, printed in many editions in seven languages for more than forty years (1570-1612), with an ever increasing number of maps.

This map comes from a 1584 edition of the atlas, though it still bears the 1570 date. Here, Africa assumes a more recognizable shape, with a more pointed southern cape. Ortelius uses the Ptolemaic sources of the Nile, two large lakes, but places them farther south. The Niger now empties into the Atlantic Ocean. The “Zanzibar” coastland is featured on the west side, as it is called (Ortelius notes) by Persian and Arab authors, but the island of Zanzibar is correctly placed off the east coast. Madagascar appears, as do the place-names of numerous towns along the coasts and in the interior, although large empty spaces begin to dominate there. No animal or plant life is indicated, but the oceans contain swordfish and a whale. Three ships in the lower right are caught in the smoke of battle. Beautifully designed and engraved, the map represents a high mark of 16th-century mapmaking.

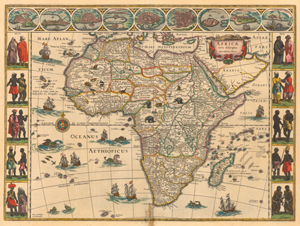

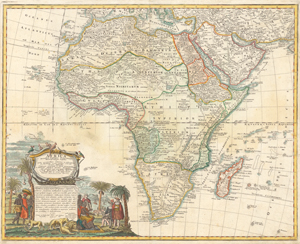

1644

1644 map

Blaeu, Willem Janszoon, 1571-1638.

“Africae nova descriptio.” Copperplate carte à figures map, with added color, 35 x 45 cm. From the second volume of Blaeu’s Le theatre dv monde; ov Novvel atlas contenant les chartes et descriptions de tous les païs de la terre (Amsterdam, 1644). Gift of J. Monroe Thorington, Class of 1915. [Rare Books Division]

One of the most decorative and popular of all early maps of Africa, from the “golden age” of Dutch mapmaking. First issued in 1630, the map was reprinted many times between 1631 and 1667, appearing in Latin, French, German, Dutch, and Spanish editions of Blaeu’s atlases. The maps and atlases of the Blaeu family business, carried on after Willem’s death by sons Cornelis and Joan, marked the epitome of fine engraving and coloring, elaborate cartouches and pictorial detail, and fine calligraphy—the most magnificent work of its type ever produced.

In the format called carte à figures, this appealing map contains oval views of, presumably, the major cities and trading ports of Africa at the time: Tangier and Ceuta (Morocco), Tunis (Tunisia), Alexandria and Cairo (Egypt), Mozambique (seaport of Mozambique), Elmina (Ghana, site of the largest and most spectacular castle in Africa built by the Portuguese), and Grand Canary (Canary Islands) Side panels depict costumed natives from areas visited along the coasts. The interior is decorated with exotic animals (lions, elephants, ostriches), which were (and still are) a major source of fascination for the public. The Nile (today’s White Nile) is shown flowing from the Ptolemaic lakes of Zaire and Zaflan. Flying fish and strange sea creatures cavort in the oceans, and the sailing ships all bear Dutch flags. Coastal names are engraved inward to give a clear, sharp outline to the continent.

Probably the most interesting cartographic feature is the identification of specific large territories or kingdoms, which have been outlined in color, including a huge Abyssinia (Ethiopia) and Monomotapa (all of southern Africa). But these seem to reflect a European sense of nationhood—something presumed and projected upon a virtually unexplored canvas—more than the actual experience of traders and explorers, who would continue to report on hundreds of smaller ethnic enclaves and political fiefdoms during the next 250 years.

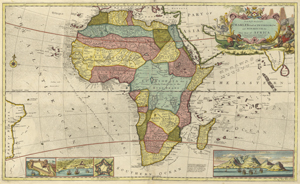

1710

1710 map

Moll, Herman, d. 1732.

“To the Right Honourable Charles, Earl of Peterborow and Monmouth, &c This Map of Africa . . . Is Most Humbly Dedicated.” Copperplate map, with added color, 56 x 94 cm. [Historic Maps Collection]

A large decorative map by a German-born English mapmaker known for a number of influential maps, including the “Beaver Map” of North America. The dedicatee, Charles Mordaunt (1658-1735), was a nobleman and military leader, commander of the English campaign in Spain in 1705. One of the characteristics of a Moll map is the textual chattiness. Here, for example, above Guinea, he writes: “I am credibly informed, that ye Country about hundred Leagues North of the Coast of Guinea, is inhabited by white Men, or at least a different kind of People from the Blacks, who wear Cloaths, and have ye use of Letters, make Silk, & that some of them keep the Christian Sabbath.” One wonders if Moll is attempting to promote the region by saying (to allay fears?) that there are (no doubt) educated, productive Christians living there.

He shows the best course for sailing from Great Britain to the East Indies “in the spring and fall” (follow the dots), as well as the general directions of winds and the months in which they prevail. Grain, Ivory, Gold, and Slave coasts are clearly identified for commercial interests. In Moll’s construction, the Niger originates in Borno Lake, possibly a reference to today’s Lake Chad. The sources of the Blue Nile are evident, but the White Nile is completely absent. The Mountains of the Moon (here, “Luna Mountains”) form the southern boundary of a vast Ethiopia, a country that is “wholly Unknown to the Europeans.” Many of Moll’s territories are different from Blaeu’s in shape and scope. As if to promote an English presence on the continent and to show that it can be protected, the map includes insets of several English forts as well as an attractive “prospect” (with a key) of the Cape of Good Hope. Like other nationalistic mapmakers, Moll has set his prime meridian on his country’s capital, but here he acknowledges the classical one through Ferro Island in the Canaries as well.

1737

1737 map

Hase, Johann Matthias, 1684-1742.

“Africa secundum legitimas projectionis stereographicae regulas et juxta recentissimas relationes et observationes in subsidium vocatis quoque veterum Leonis Africani. . . .” Copperplate map, with added color, 45 x 57 cm. [Historic Maps Collection]

Hase became a professor of mathematics at Wittenberg in 1719 and worked for the heirs of the great German cartographer Johann Baptiste Homann (“Homann Heirs” as the map publishing firm was known) beginning in the 1730s. In his map of Africa, “according to the most recent reports and observations,” Hase identifies several territories or kingdoms but not all have been accentuated by the colorist [see the dotted lines]. The central part of Africa is marked incognita; Blaeu’s two lakes have been replaced by a long, narrow one (Marawi) in the general area where future explorers will find Lake Nyasa, which is also called Lake Malawi.

Ultimately, it is the cartouche area of Hase’s map that captures the viewer’s attention. A discussion (interview?) takes place between European traders, one in a chair, and a local chief or king, seated on the back of a kneeling supplicant on an ornate mat or rug. A view of Table Bay and Cape Town, with its distinctive Table Mountain, at the Cape of Good Hope provides background. A lion family, tortoise, crocodile, and snake populate the foreground, while elephant tusks and various birds decorate the title box. The African youth in the palm tree appears to be lowering a pot, perhaps identifying the tree as an oil palm, native to West Africa, and thus indicating another commercial commodity: palm oil.

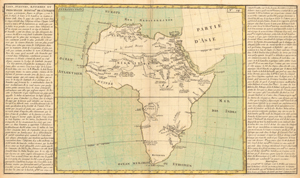

1787

1787 map

Clouet, J. B. L. (Jean-Baptiste Louis), b. 1730.

“Lacs, fleuves, rivières et principales montages. de l’Afrique.” Copperplate map, with added color, 31 x 35 cm., with side panels of text on larger sheet. From Clouet’s Géographie moderne avec une introduction (Paris, 1787). Gift of John Delaney. [Historic Maps Collection]

A bare-bones school map of the geographic features of Africa as known toward the end of the eighteenth century. Abbé Clouet was a member of the Académie des Sciences of Rouen, and his map suggests what French schoolchildren might have been taught about Africa just before the French Revolution. In his less-is-more approach, he has attempted to remove fictitious and/or inaccurate elements in favor of a few known, inherited geographic facts, though even some of those are rather weak. He has also eliminated the clutter of surrounding islands. In his accompanying commentary, he presents a more open attitude towards map construction and the maker’s responsibility for weighing evidence.

The text in the side panels is actually engraved, not printed with type. Clouet devotes the left side to a discussion of the Nile, its sources and significance, making reference to the opinion of the great French cartographer Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville (1697-1782). D’Anville jetté des doutes (“threw doubts”) on the discovery of Nile sources in the mountains of Ethiopia, which the Portuguese missionaries Pedro Páez (1564-1622) and Jerónimo Lobo (1596?-1678) had confirmed in the seventeenth century; rather, he preferred l’ancienne opinion which favored the Mountains of the Moon. Clouet labels the Ethiopian source as the moderne one, though he also shows the White Nile flowing from the Montagnes de la Lune. The varying level of the annual summer flooding of this major river, Clouet notes, determines fertility or famine for the country.

In the right-hand panel, among his descriptions of other rivers, Clouet states that the Niger flows to the east. (Ten years later Mungo Park would prove that it does flow east, but then bends south.) He hopes that one day all confusion about the relationship between the Gambia and Senegal rivers will be resolved. The Atlas Mountains, shown prominent across Barbary, are deemed the principal ones in Africa, for there is no evidence yet of Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya, the continent’s highest mountains.

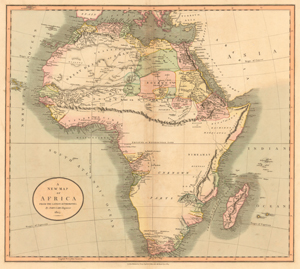

1805

1805 map

Cary, John, ca. 1754-1835.

“A New Map of Africa from the Latest Authorities.” Copperplate map, with added color, 45 x 51 cm. From Cary’s New Universal Atlas (London, 1808). [Historic Maps Collection]

A turn-of-the-century no-nonsense British map that clearly presents the geographical gaps that will consume the attention of explorers, the majority of them British, for the rest of the century. From his business in the Strand in London, Cary developed a reputation for creating beautifully printed, clean-looking and accurate maps that presented only the most recent geographical information. His “General Map” (1794) of the British Isles was the first to use Greenwich as the prime meridian, which is the standard observed today. (The time at this meridian is known as GMT, Greenwich Mean Time, which establishes the base time for other time zones around the world.)

In this map of Africa, the Mountains of the Moon are shown to be a continuation of the Mountains of Kong. (An area of the Ivory Coast, Kong was a prominent kingdom in the eighteenth century.) They appear as a formidable barrier to the rest of the continent. [See the discussion of the Mountains of Kong in the “Central Africa” section.] The sources of today’s Blue Nile, firmly established by James Bruce in his travels in the 1770s, are noted; the White Nile appears to gather itself from foothill streams of the lunar mountains. Caravan routes cross the Sahara, but no European has used them yet to reach Tombouctou (Timbuktu). At the time Cary was publishing this map (June 1, 1805), Scotsman Mungo Park was making his second expedition to the Niger River, which ended with his death at the Bussa Rapids (Nigeria).

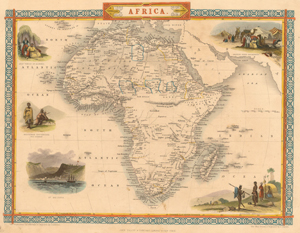

1851

1851 map

Tallis, John, 1817-1876.

“Africa.” Steel engraved map, with some added color, 22 x 30 cm., with five vignettes. From Tallis’s The Illustrated Atlas, and Modern History of the World, Geographical, Political Commercial & Statistical, edited by R. Montgomery Martin (London, 1851). [Historic Maps Collection]

Issued to coincide with the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, Tallis’s atlas was regarded as a tour-de-force of the mapmaker’s art, scientific in intent but visually attractive: one of the most decorative atlases of the nineteenth century. The maps were drawn and engraved by John Rapkin, and the vignettes were created and engraved by various prominent artist-illustrators.

About the continent of Africa, Martin writes in a note accompanying the map in the atlas:

More than five-sixths of the region are still unknown to European geographers. . . . Of the alleged Mountains of the Moon we know nothing. Vast sandy wastes with occasional green and habitable spots characterize Africa. . . . The chief streams of which we have any definite and accredited account are the Nile, Niger, Joliba, Senegal, Gambia, Congo, Orange, Quilimane and the Haines. The Nile rises in Abyssinia and enters the Mediterranean at Rosetta. The Niger has its source in the Kong Mountains and enters the Atlantic after 1,660 miles. Charting its course has cost many British lives. . . . In the known parts of Africa alone 150 languages are spoken.

Between the time of this and Cary’s map, British explorers have crossed the Sahara, descended the Niger to its outlet in the Gulf of Guinea, and visited large areas of west and southern Africa. Not surprisingly then, the map’s vignettes show an Algerian family, a Bedouin Arabs’ desert encampment, two different Hottentot tribes (Bosjeman and Korranna) of southern Africa, and a view of the island of St. Helena. Important as a port of call for ships returning to Europe from the East Indies, the island declined in importance after the Suez Canal opened in 1869.

1852

1852 map

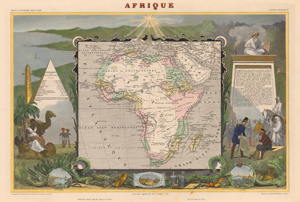

Levasseur, Victor.

“Afrique.” Steel engraved map, with some added color, 21 x 23 cm., set within a larger pictorial framework. From Levasseur’s Atlas national illustré des 86 départements et des possessions de la France (Paris, 1852). [Historic Maps Collection]

First published in 1845, this map underwent little change in subsequent editions through 1869. An interesting contrast to the preceding English map of the same period, this French version appears subordinate to its surrounding pictorial (and political) representations. For its date, the map’s geographical detail is poor and rather limited. It has not benefited, for example, from the published route maps of French explorer René Caillié’s travels (1824-1828) to Timbuktu and beyond.

The decorations, however, are intriguing and revealing. The hot African sun reigns over the continent. On the right, a French military officer is showing an armed Arab a map or other document (a surrender document?), while French soldiers and Arab horsemen look on. Seated above them on a shelf is a turbaned Muslim holding a tablet lettered CORAN (Koran). Along the bottom is a display of fruit, foliage, and animals, including small oval views of Alexandria, Cairo, and Algiers. An African woman, with lions at her feet and a camel and ostrich at her side, is seated on the left. An obelisk and pyramid (bearing current population statistics) recall ancient history. The French text notes that the descendants of Cham, one of Noah’s sons, spread through the continent, first in Egypt and Libya, and that Algeria (recently conquise by the French) will have a glorious future. Like its English counterpart (the Tallis atlas), Levasseur’s work is considered to be one of the last great decorative atlases.

1856

1856 map

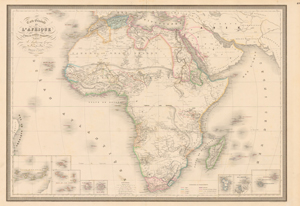

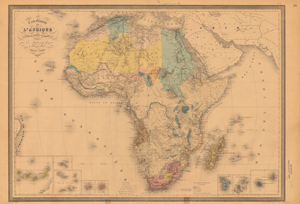

Andriveau-Goujon, J.

“Carte générale de l’Afrique, d’après les dernières découvertes.” Steel engraved map, with some added color, 58 x 85 cm. Probably issued in Andriveau-Goujon’s Atlas classique et universel de géographie ancienne et moderne . . . (Paris, 1856). [Historic Maps Collection]

1880 map

Andriveau-Goujon, E. (Eugène), 1832-1897.

“Carte générale de l’Afrique, d’après les dernières découvertes.” Steel engraved map, with some added color, 59 x 86 cm., mounted on linen. [Historic Maps Collection]

The quarter century gap between the dates of these two maps was probably the most productive period for African exploration in the history of the continent. The geographic gains from the expeditions of David Livingstone (southern), Sir Richard Francis Burton and John Hanning Speke (lake region), and Henry Morton Stanley (central) are evident in the later map, as is the advance of European influence in (and control of) territories, depicted by the color-coded areas. The 1856 map contains a shaded line across the north-central part of the continent, demarcating Arab countries from pays des Négres. Note also how the central lake area has developed by 1880 from one vast Lac d’Ouniamessi into separately identifiable lakes. More often spelled “Unyamuezi” or “Unyamwezi,” Ouniamessi means “land of the moon”—hence, the lake, later known as Lake Tanganyika, was thought to be in the land of the moon where the Mountains of the Moon existed. Stanley’s expedition (1887-1889) to aid the Equatorian governor Emin Pasha would encounter the Ruwenzori Mountains, located just north of the equator between Lakes Albert and Edward, the mountain group most closely associated today with the fabled Mountains of the Moon.

1880