Prester John

The legend of Prester John (also Presbyter John) held such sway over the European imagination from the 12th through the 17th centuries that most historians believe it developed around some kernel of fact. The story told of a Christian patriarch and king said to rule over a Christian nation lost amid Muslims and pagans in the Orient. Reportedly a descendant of one of the Three Magi, Prester John was a generous ruler and a virtuous man, presiding over a realm full of riches and strange creatures (centaurs, Amazons, giants), in which the Patriarch of St. Thomas resided. His kingdom contained such marvels as the Fountain of Youth, and it even bordered the Earthly Paradise. Among his treasures was a mirror through which every province could be seen. There were no poor people, no dissensions, no vices in his dominions.

Part of the evidence for Prester John’s existence is a letter that he purportedly wrote to the Byzantine emperor Manuel I, in which he claims to be the greatest Christian monarch under heaven and describes at length the wonders of his empire. The popularity and diffusion of this letter, which circulated around 1165, is evident from the fact that almost a hundred medieval manuscript copies of it are known in libraries across Europe. At first, Prester John was believed to be in India. After the coming of the Mongols to the Western world, accounts placed the king in Central Asia; no doubt, over time, there was some confusion with Genghis Khan, the Mongolian founder of the largest contiguous empire in world history. Eventually, Portuguese explorers convinced themselves that they had found him in the Christian country of Ethiopia, which had been mistaken for India since at least the time of Virgil.

Functionally, his locus never really mattered, for Prester John became a symbol to European Christians of the Church’s universality, transcending culture and geography to encompass all humanity. During those “dark” centuries, his legend inspired Europe’s explorers, missionaries, scholars, and treasure hunters, while his kingdom remained out of reach—as was Africa.

On maps of Africa, Prester John’s kingdom appeared through the 17th century in the general area of today’s Ethiopia. When academics proved that there was no actual connection between Prester John and the Ethiopian monarchs, the fabled king disappeared from the maps for good.

1603

1603 map

Ortelius, Abraham, 1527-1598.

“Presbiteri Iohannis, sive, Abissinorum Imperii descriptio.” Copperplate map, with added color, 35 x 42 cm. From Ortelius’s Theatrum orbis terrarium . . . (Antwerp, 1603). Reference: Norwich, Africa 11. Purchase aided with funds provided by Bruce Willsie, Class of 1986. [Historic Maps Collection]

Often called the Prester John map [see the note on him above], the map was not added to Ortelius’s landmark atlas till the 1573 editions. This 1603 copy, as is often the case with early Africa maps, shows that no changes were made in the interval. The many notes added by Ortelius provide insights into the prevailing myths of the time. For example, he says that the Niger River, shown flowing north from Lake Niger (Niger lacus), goes underground for sixty miles and emerges in Lake Borno (Borno lacus); that sirens and sea gods live in Lake Zaire (Zaire lacus); and that the sons of Prester John were kept captive by rulers at Mount Amara (Amara mons). Prester John’s coat of arms occupies the upper right corner. Oddly, an Egyptian dhow is pictured off the west coast. This is certainly one of the maps that Jonathan Swift had in mind when he quipped in verse:

So Geographers in Afric-maps

With Savage-Pictures fill their Gaps;

And o’er uninhabitable Downs

Place Elephants for want of Towns. (On Poetry: A Rhapsody, 1733)

1730

1730 map

L’Isle, Guillaume de, 1675-1726.

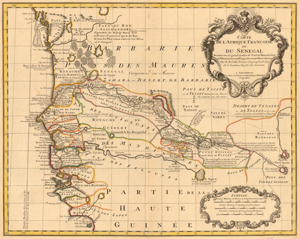

“Carte de l’Afrique françoise ou du Senegal dressée sur un grand nombre de cartes manuscrits et d’itineraires rectifiés par diverses observations.” Copperplate map, 48 x 60 cm., with added outline color. Probably from L’Isle’s Atlas nouveau . . . (Amsterdam, 1730). [Historic Maps Collection]

De L’Isle or Delisle (as his name is often spelled) was a pupil of Jean Dominique Cassini, whose linking of astronomy with geography enabled greater accuracy in the fixing of locations. Delisle’s application of his interests in astronomy and mathematics to mapmaking earned him recognition as the first “scientific cartographer.” He left areas blank on his maps where he had little or insufficient information, hence eliminating fictional or imaginative geography. He continually updated his maps to reflect new knowledge.

Originally drawn by Delisle in 1726, this later edition of the map was published by Cóvens and Mortier. The Senegal/Gambia area, where the Portuguese previously had maintained trading posts for more than a hundred years, was the scene of intense logistical maneuvering by the French and English during the 18th century in order to promote their commercial interests. The map reflects the contemporary French view; Delisle is happy to point out Rocher de Guingou, for example, the farthest spot the English have reached on the Gambia River. Of note are the island fort of Saint-Louis, France’s first settlement in Senegal, and the island of Gorée, a major slave transit port. A number of distinct native regions are named along the coast; but, except for areas along the Senegal and Gambia rivers, it is obvious that very little inroad into West Africa has been made beyond one or two degrees longitude. The region above the heart of the map is called the land of the Moors, Arab country. Timbuktu is shown at the far right on the bend of the Guien River, which on later maps will be identified with, and called, the Niger. Both the Senegal and Gambia rivers are traced to lakes, but these assumptions will prove to be erroneous. The real value of the map lies in the great number of place-names identified along the coast and the rivers.

The Mountains of Kong

This West African east-west range of mountains was first created by English cartographer James Rennell on his 1798 maps depicting the travels of Mungo Park, who had been sent by the African Association in 1795 to explore the Niger River. Subsequently, the range appeared on almost all Africa maps of the 19th century. Although the mountains were completely fictional, the myth of their existence was perpetuated by later explorers like René Caillié, Hugh Clapperton, and John and Richard Lander. Not until the late 1880s was the range completely eliminated from maps after the defining expedition (1887-1889) of Louis-Gustave Binger, the French officer and explorer who claimed the Côte d’Ivoire for France and was appointed its governor in 1893.

Rennell (1742-1830) was considered to be one of the most prominent geographers of his time, known for critical evaluation of his cartographic sources. Park’s observation of very distant mountains situated in the kingdom of the Kong helped substantiate Rennell’s theory that the Niger, prevented by mountains from reaching the ocean, flowed east for a great distance, emptying into lakes and desert. Later explorers to the area believed they were merely confirming what earlier eyes had seen. As this example demonstrates, a geographic theory based on selective information and stamped with the imprimatur of a major cartographer could lead to an authoritative, but inaccurate, map tradition in African cartography.

1813

1813 map

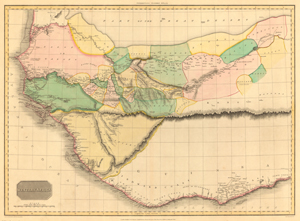

Pinkerton, John, 1758-1826.

“Western Africa.” Copperplate map, with added color, 49 x 68 cm. From Pinkerton’s A Modern Atlas, from the Latest and Best Authorities . . . (London, 1815). Gift of Bruce Willsie, Class of 1986. [Historic Maps Collection]

The Niger River (also called the Joliba) makes a fuller appearance here; gone are Delisle’s source lakes for the Gambia and Senegal rivers. The source (head on the map) of all three rivers is now shown to be the Kong Mountains [see note on them above], ranging horizontally across the entire map. Much of the colored area reflects the cartography of Scotsman Mungo Park’s map from his first expedition (1795-1797). At the time Pinkerton published his atlas, Park had already embarked on a second journey (1805-1806), following the Niger more than a thousand miles to Bussa Rapids (in today’s Nigeria), where he was killed by natives. News of his death eventually reached the coast, but, unfortunately, his journal was never recovered. Hence, “from the latest and best authorities” does not always mean “contemporary.”

Over the next two decades, the Frenchmen Mollien and Caillié and the Englishmen Clapperton and Lander would bring back the geographical information to complete much of the empty space on this map and to correct some of its errors.

1828

1828 map

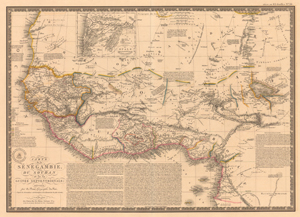

Brué, Adrien Hubert, 1786-1832.

“Carte de la Sénégambie, du Soudan et de la Guinée Septentrionale.” Copperplate map, with added outline color, 35 x 50 cm. From Brué’s Atlas universel de geographie (Paris, 1830). [Historic Maps Collection]

French cartographer and publisher Brué followed the Delisle tradition of maintaining high standards in his mapmaking by bringing a critical approach to his material. Here he acknowledges his cartographic problems at the outset: his effort is a combination of elements often incomplete or contradictory; in the area covered by his map, one is almost always reduced to hypotheses, but less so along the coasts than the interior. In short, more déterminations astronomiques (measurements of latitude and longitude) are needed. Still, among the major sources he lists, such as Mollien, Laing, Denham and Clapperton, some are unusually contemporary (1827-1828), suggesting the rapid growth of knowledge of that part of the continent based on the direct observations of explorers. Appropriately, Brué follows a number of interior place-names with question marks. European settlements are letter-coded along the coast, reflecting the ontinuing jockeying of position among the colonial powers.

1860s

1860s map

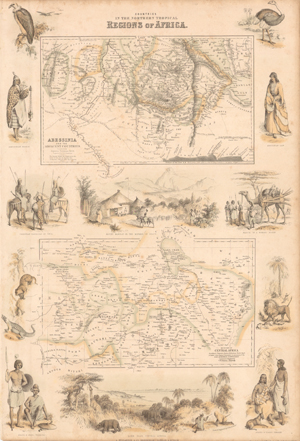

A. Fullarton & Co.

“Countries in the Northern Tropical Regions of Africa” (two maps on one sheet). Engraved map with etched vignettes, and with some added color, 48 x 33 cm. (sheet size). From Fullarton’s Royal Illustrated Atlas of Modern Geography (Edinburgh, 1864-1872). [Historic Maps Collection]

The appeal of Fullarton Company maps mostly derives from the “local color” of their vignettes, which convey the tone and spirit of the images found in the sources of their geographic information: explorers’ published narratives. The second map, “Map of Part of Central Africa,” depended on the work of a number of explorers, including Clapperton, Denham, Richardson, and Barth, as well as documents held by the Royal Geographical Society in London. Here Lake Chad takes prominence, along with many of its feeder streams and rivers, although the eastern third of its shoreline has not been surveyed yet. Numerous distinct native kingdoms are named and located, as far west as the Niger River, as far south as its great eastern fork, the Chadda River (today’s Benue in Nigeria), and as far east as the watershed of the Shari River (or Chari) —still well north of the vast Congo region that Stanley would traverse in the next decade.