“Greegree-Man of Ma Yerma / Greegree-Man of Ba Simera”

The guide insisted upon seeing the greegree man of the town, which demand being acceded to, after very violent opposition, a man (dressed as is represented in the accompanying drawing) made his appearance. He was less disguised, though more hideous to look at, than Ba Simera’s; his head supported an enormous canopy of sculls, thigh bones, and feathers, and his plaited hair and beard, twisting like snakes, appeared beneath it. His approach was notified by the tinkling of hawk’s bells, and jingling of pieces of iron, which, suspended to his joints, kept time with his actions. He made several circuits round the assembly, and then approaching the middle, demanded the cause of his summons, with which being made acquainted, he waved his rod several times in the air, and made his way into the bush, where he remained nearly a quarter of an hour. On his return, he spoke at some length, and concluded by naming the man who had stolen the gun. . . . [pp. 62-63]

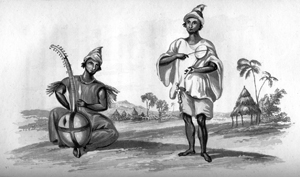

“Jelle-Man of Soolimana / Jelle-Man of Kooranko”

At parting, he [the king] sent his griot or minstrel to play before me, and sing a song of welcome: this man, of whom I give a sketch, had a sort of fiddle, the body of which was formed of a calabash, in which two small square holes were cut to give it a tone; it had only one string, composed of many twisted horse-hairs, and although he could only bring from it four notes, yet he contrived to vary them so as to produce a pleasing harmony. . . . [p. 148]

“Yarradee, War-Master of the Soolimas”

I was scarcely seated when my old friend, Yarradee, (habited in rather a more costly manner than when I first beheld him at the camp in the Mandingo country) mounted on a fiery charger, crossed the parade at a full gallop, followed by about thirty warriors on horseback and 2,000 on foot, the latter making a precipitous rush, and firing in all directions. . . . Yarradee now alighted from his horse, and seizing his bow, pulled the string to the full extent, affecting to shoot an arrow at some distant object; he appeared to watch it on tiptoe with eager expectation till it reached its destination, when he gave a leap and a smile of satisfaction; then striking his breast with his right hand, and distorting his naturally ugly visage into a most hideous grin, he beckoned his war-men to follow, which they did with a shout that rent the skies. . . . [pp. 229-30]

“Soolima Female Dancers”

The females were to be seen in groups ready decked for the evening dance. . . . The wool, or hair, was divided, and arranged into a number of small balls, which were tipt, or surmounted, by beads, cowries, and pieces of red cloth, the interstices being smeared nearly an inch thick with fresh butter, a most disgusting practice, adopted as a substitute for palm-oil; the ankles and wrists were beautifully ornamented with strings of pound beads of various colours laced tightly together in depth about fifteen or twenty strings. The public dancing and singing women were distinguished from the others by the profusion of their head ornaments, their large gold ear-rings shaped like a heart, and rich silk or taffeta cloths and shawls, the latter of which, suspended from the shoulders, and supported on the arms, were brought into graceful action in the dance. [pp. 310-11]

“A Sangara Soldier / A Sangara Chief”

The country of Sangara, which is situated on the opposite side of the river Niger, is one of considerable extent, and is rich in cattle, horses, pasturages, corn and rice-fields. The inhabitants, who are subdivided into numberless petty tribes, are as warlike a race as the Soolimas, and far surpass them in enterprise; so that the Soolimas must have become their tributaries, had the Sangaras been a united nation. They are so fond of war, that the Soolima king can be reinforced at any time, with a month’s notice, by an army of 10,000 men from Sangara; they are taller and better-looking men than the Soolimas, whom they resemble in their costume, the chiefs only declining to disfigure themselves with the ditch-dyed cloth. [pp. 371-72]