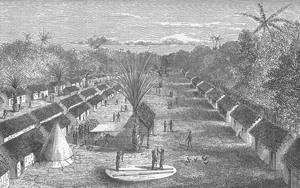

“Village of Kitata, Tanganyika Lake”

No imported cloth was to be seen at the village of Kitata, the people wearing skins, bark cloth, or cotton of their own manufacture. The people suspend their clothing round the waist by rope as thick as the little finger, bound neatly with brass wire. Their wool is sometimes anointed with oil in which red earth has been mixed, giving them the appearance of having dipped their heads in blood. [Vol. 1, p. 275]

“Crossing the Lugungwa River”

Many of the streams were particularly beautiful, especially the Lugungwa, a short way below the ford, where it had cut a channel fully fifty feet deep in the soft sandstone and not more than eight feet wide at the top. On the projections of its cliff-like sides most lovely ferns and mosses grew, and large trees on both banks mingled their branches and formed a perfect arch of verdure over the river. . . . And it was needful of me to keep in the rear of the caravan in order to prevent my men from straggling. With all my care they often eluded me and lay hidden in the jungle till I had passed in order to indulge in skulking. [Vol. 1, pp. 327-28]

“Village of Manyuéma”

And here we seemed to be in an entirely new country. . . . The huts were ranged in long streets, sometimes parallel and at others radiating from a large central space; their bright red walls and sloping roofs differing from those hitherto met with. And in the middle of the street were palaver huts, palm-trees, and granaries. In their dress the people were different from any I had previously seen. The men wore aprons of dressed deerskin about eight inches wide and reaching to their knees. They carried a single heavy spear and a small knife with which to eat. . . . The heads of the males were generally plastered with clay so worked in with the hair as to form cones and plates. [Vol. 1, pp. 352-53

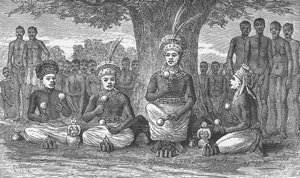

“Warua Waganga”

My attention was attracted one morning by a tinkling, similar to that of a number of cracked sheep bells, and looking out I saw a Mganga, or medicine man, ambling round the village followed by his train. He was dressed in a large kilt of grass cloth, and suspended round his neck was a huge necklace composed of pieces of gourd, skulls of birds, and imitations of them roughly carved in wood. His head-dress was a broad band of parti-coloured beads surmounted by a large plume of feathers; and his face, arms, and legs were whitened with pipe-clay. On his back he carried a large bunch of rough conical iron bells, which jingled as he paraded the village with jigging and prancing steps. He was followed by a woman carrying his idol in a large gourd, another with a mat for him to sit upon, and two small boys who bore his miscellaneous properties. When he appeared all the women turned out of their dwellings. . . . [Vol. 2, pp. 81-82]

“Jumar Merikani’s Tembé”

This was Jumah Merikani, who proved to be the kindest and most hospitable of the many friends I found amongst the Arab traders in Africa. He conducted me to his large and substantially built house, situated in the midst of a village surrounded by large plantations of rice and corn, and did everything in his power to make me feel thoroughly at home and comfortable. Jumah Merikani had been here nearly two years, trading in ivory, which was fairly plentiful and cheap. Being an intelligent man and having travelled much since leaving Tanganyika, he and some of his men were able to give me a vast amount of geographical information. . . . [Vol. 2, pp. 54-55]

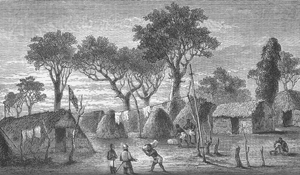

“Camp at Lupanda”

Camping for that night in the jungle, we next marched to Lupanda, three days being occupied on the road. . . . Just outside a village I saw a dead python thirteen feet eight inches in length, but not of great girth. At none of these villages were we allowed to enter. . . . The place I had chosen for my camp was near the path, and the whole caravan [slave gang] passed on in front, the mournful procession lasting for more than two hours. Women and children, footsore and over-burthened, were urged on unremittingly by their barbarous masters. . . . [Vol. 2, pp.145-47